Anti-fascist tech is possible: Trans tech creators show how to urgently center community needs

Or, at least, the best of ’em do. Oliver Haimson’s new book, “Trans Technologies” from MIT Press, boldly asks what tech could look like reimagined as a tool of liberation. He sat down with ESC KEY .CO for a (very long) chat to reveal a (very timely) bit of the answer.

This past Wednesday, on a cold winter evening, I queerly power-walked across London’s Waterloo Bridge, over the frigid-looking Thames, along with a fast queer friend. As it so happens, I was procrastinating on finishing this draft.

My friend had secured last-minute tickets to attend a sold-out book event at Southbank Centre. The topic? What’s wrong with love. I was late in completing a feature about another author (yes, indeed, this one). I thought, sure, I’d like to procrastinate by attending an event with a different author about the one thing I find even more painful than writing (yes, love).

There wasn’t an empty seat in the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The visibly queer and trans audience was largely drawn there for the same reason I was. That’s the undeniable witty charisma of the author, Shon Faye, presenting her dazzling new book, “Love in Exile.” And also because of the widespread sense that everything wrong with our world has also broken some of the most intimate facets of our lives.

Faye spoke about why she blended memoir — her romantic experiences as a trans woman dating in modern Britain — with political critique. And throughout the book, she draws on the work of cultural theorists — including Mark Fisher’s “Capitalist Realism,” among others — to discuss some of the systemic issues underlying everything that makes the act of finding love feel so off for so many. Or, as Faye bluntly framed it that evening, we’re trying to find love in a “techno-capitalist dystopia,” she said with a wise chuckle. The hall full of broken hearts laughed, too, the kind of laugh that betrays you know something painfully well.

Certainly, the fact that this all feels like a “techno-capitalist dystopia” is an increasingly common view among singletons, probably explaining the lack of an empty seat in the room. Faye also has a way of taking personal themes and making connections to broader economic forces many people miss.

That’s one reason why, as I slowly stepped with the crowds toward the hall’s exits, Faye’s words had me thinking about the broader cultural context that greets another newly released book. Yes, the one I’d spent the past few weeks sitting with. I was also seated in row H, which happens to be the first letter of the last name of that book’s author. (My mind makes remarkable connections when I’m avoiding a deadline!)

The brilliant book haunting me that night was “Trans Technologies,” released on February 25 from MIT Press and freely available now via open access. The “H” labeling my row stood for Oliver Haimson, assistant professor at University of Michigan School of Information, where he directs the Community Research on Identity and Technology Lab.

“He goes deeper than the obvious facts of exclusion and explores how trans tech creators build alternative worlds.”

Aside from the looming release date, Haimson’s book has also been living rent-free in my mind for a few more meaningful reasons. On one level, it’s a surprisingly entertaining read on the wide world of trans tech creators, as Haimson calls the subjects he interviewed for the book. I say surprising because typical academic surveys can be as illuminating for experts as they are uninviting to a wider audience. This is decidedly a book aiming for a wider audience. On a deeper level, it’s a book that shows through dozens of examples what the principles of better tech can look like in practice.

The day after the reading, it felt like both authors were meeting for a latte at some cafe in the back streets of my mind, where they’ve remained in dialogue about what we should be thinking about the techno-capitalist dystopia. I draw no direct parallel between the styles or themes of their distinct books. But both swim in a similar milieu of brilliant minds grappling with our present dystopia. And both resist the total doomer vibes. In looking at the state of love, Faye draws a line to capitalism, sings of the joy of queer friendships and encourages a more spiritual perspective on life. Similarly, in looking at the way mainstream tech excludes marginalized people, Haimson goes deeper than the obvious facts of exclusion and explores how trans tech creators build alternative worlds.

If you’ve also got the sense that the way tech works right now is making things worse in many areas of our lives, then trans tech creators show us different principles in action for urgently centering on community needs.

Equally, understanding where trans tech fails, as it often does, makes clear why we need to widen the scope of our imagination beyond the current market dynamics that make these alternative visions so hard to sustain.

It’s a direct challenge to what we might call our internet oligarchy, that cozy club of billionaires whose platforms have been sold to us as de facto public squares while remaining private fiefdoms. Their effective monopolies keep us locked in walled gardens, full of carnivorous plants waiting to eat our eyes. And all the while, the platforms work only well enough that we stay until they can extract that much more of our attention and data for their profit. The problems have only intensified as platforms such as FKA Twitter under Elon Musk and Meta in Mark Zuckerberg’s “bro-up” era betray the true priorities, as a democratic crisis unfolds under the second Trump administration. It’s rolling back moderation, emboldening the most vengeful and hateful internet users and making everything worse for everyone.

No matter how you identify, the moment makes clear why the oligarchic and fascist currents across the internet aren't serving anybody that well except for these overlords.

Last month, I wrote a piece of tech analysis disguised as a drag competition (yes, that’s the absurd concept behind the campy new Hype Ball series). I drew on a decade of my own reporting about dating apps and social media — previously in outlets including Vice, The Washington Post and Them — to discuss the perverse incentives that have made dating apps feel like a hellscape. “I viewed my role as an accountability journalist who might motivate these platforms to get a touch less discriminatory, a hair more livable for marginalized folks,” I wrote alone in my flat this Valentine’s Day. “I’ve kept asking the same questions. Little has changed.” Indeed, far from tens across the board.

I insert myself here only because I sense you might be reaching similar conclusions in your line of work. And this is where we can deeply relate to Haimson’s evolution over the course of his academic life: “For the first five or so years of my career as a researcher, I was really trying to understand how we can make these mainstream platforms more inclusive,” Haimson tells ESC KEY .CO in the full interview below. “I mean, I was always resistant to working with Facebook or Meta, but now it's clear they just never really cared.”

This is about the point when someone in the metaphorical audience interrupts with a “yeah, yeah, yeah, enshittification!” It’s also when I find the vogue repetition of that buzzword gets a tad tedious. That’s especially the case when the context is marginalized folks, who have often found these platforms enshittified from the start, even when we’ve carved out corners of these algorithmically curated spaces that have allowed us to explore our identities and seek some semblance of community support when it’s not readily available around us.

It’s not the concept itself that’s the issue. It’s how often it is conjured by lazy analysts who cite it to explain away our present woes without any further intellectual engagement with what alternatives could look like. Too often, they conclude the conversation with the problems. It’s as if the guy who coined the term in the first place, Cory Doctorow, doesn’t have his own ideas on what potential solutions could be — he does. (In fact, Doctorow’s ideas in the context of digital platforms include the “end-to-end principle,” the “right to leave” and so on.)

Certainly, enshittification accurately describes how digital platforms initially create value but degrade over time as profit motives take precedence. But it’s describing a symptom of deeper systemic issues in the economic and political forces around tech. And by stopping the analysis at the diagnosis of those symptoms — something Doctorow avoids in his extensive work but where many people citing him tend to stop — we risk overlooking the underlying system that drives the phenomenon. We risk adopting “solutions” rooted in the same rotten soil.

Those lazily citing enshittification often accurately speak to the pains experienced by a growing number of privileged users in the Global North, but then overlook the forces transforming human creativity and labor into devalued inputs across the entire digital supply chain. Behind the scenes, new platforms are also often enshittified from the start for the laborers. Behind every slick “AI” platform, for instance, lies a supply chain of invisible workers: data labelers in Global South “content farms” making pennies to tag disturbing content, gig workers algorithmically managed into precarity and content creators whose work trains the very systems that make creative work more precarious.

This pattern is pervasive across society, currently. The same economic forces transforming once-beloved apps into far-right hellscapes are driving the financialization of housing, the hollowing out of news organizations, the algorithmic management of labor and the list goes on.

In joining up these dots, the question becomes not “Why did X platform get worse?” but “What alternative design, ownership and governance models might align technologies with human needs instead of extraction?”

While more and more of the general public now find tech culture toxic and yes, enshittified, that’s not new for those who have long been marginalized and excluded by Big Tech. Many have been DIY-ing since day one to create alternatives or something the dominant imagination couldn’t have allowed. In simpler terms, complaining about how bad things are, no matter how accurate the complaint is, doesn’t change them. That requires action. It’s about as helpful as someone buying fast fashion while saying “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism.”

I say that because “Trans Technologies” is not a book only about tracking the symptoms. It asks the bigger questions. Then shows us what some answers look like.

This is among a rare number of studies showing how those most marginalized by modern tech are already working to create different models despite the legislative attacks, the violence, the vitriol. Through the scope of the technologies he explores here and the accessibility of his prose, Haimson blew my mind. And he’s sure to expand your imagination about what tech can achieve when we think bigger than the internet oligarchs want us to. This is also a book that will make you chuckle a few times at the occasional trans internet joke — and at least one delightful moment of shade.

“You use ‘trans technology’ as if it were a thing. But that's not a well-defined phrase now,” trans tech pioneer Lynn Conway bluntly told Haimson during his interview with her for the book. She wasn’t wrong, Haimson writes in the first chapter. But that academic shade sets the tone for a book that’s challenging the conventional way both users and creators think about tech. It’s equal parts rigorous ethnography and cultural intervention.

After interviewing more than 100 trans tech creators in one year of research, Haimson emerges with something that thankfully does not read like the early works of Judith Butler (no shade). By which I mean to say, this is not a jargon-dense work written for the jaw-stroking scholars in the proverbial Ivory Tower. Rather, this is a precisely and accessibly written field guide to what alternative tech futures could look like. And it asks, compellingly, what tech looks like when it’s not in service of oppression but collective liberation.

First proposing the term “trans technologies” around 2018, Haimson’s extensive research has helped us draw some conclusions in the context of trans tech.

He offers two interlocking definitions for what makes technology truly trans: the practical (“technology that meets trans people's needs and is made by, for, and/or centering trans people”) and the theoretical (technology that “changes what technology means and opens up new possibilities for what it can do by foregrounding change and transition”). This dual framework allows for examining both concrete tools addressing specific challenges and more experimental works that reimagine technical possibilities altogether.

“At their best, trans tech creators demonstrate a vision for tech that extends, rather than limits, our agency.”

Speaking to me in the weeks leading up to the book’s release, Haimson said the thing that surprised him the most from his year of interviewing trans tech creators was the scope of trans technologies to study.

Yes, this includes transition-tracking apps that help users monitor hormone changes, but it goes everywhere from richly esoteric games to “do not travel” maps. Think browser extensions that automatically replace deadnames; healthcare resources pinpointing “informed consent” providers nearby; mutual aid platforms redistributing urgently needed community support; voice-training tools for gender expression; indie game jams processing complex emotions; and digital archives preserving histories systematically erased elsewhere. Some, like the Transgender Usenet Archive, embrace what creator Avery Dame-Griff calls “fuzziness,” the expectation that categories themselves will shift and change over time; a radically different approach than the rigid data structures undergirding, say, Facebook’s empire. Others, like Trans Defense Fund LA, respond directly to material threats with practical harm reduction.

What unites many of the best examples is a collectivist approach, tools pointed toward survival and joy as opposed to individualist isolation and extractive business models.

At their best, trans tech creators demonstrate a vision for tech that extends, rather than limits, our agency.

A few chapters into “Trans Technologies” and the principles Haimson writes about kept bringing to my mind another open-access book from MIT Press. That’s Sasha Costanza-Chock’s 2020 tome “Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need.” (Over the past few years, I’ve interviewed Costanza-Chock about a couple different hellscapes, #TravelingWhileTrans and TSA hell as well as Google’s transphobic autocomplete search results hell.) I might’ve let out an audible “of fucking course! yes!” when Haimson draws an explicit line from his findings to the design justice framework in the third chapter, “Privilege and Exclusion in Trans Technology Design.”

Citing Costanza-Chock, he writes that design justice involves asking three key questions throughout all stages of design work: “Who participated in the design process? Who benefited from the design? Who was harmed by the design?”

Here Haimson makes the case for design thinking beyond a lone tech creator’s often privileged view of wider community problems. It’s not enough that trans tech merely be made by trans people, though that’s important. In the chapter, he observes that 78% of the trans tech creators in his sample were white, with trans tech creators typically more highly educated than the trans population as a whole. “Trans technology design can thus further marginalize some trans people,” he writes. “Individualist design processes create technologies that meet individual needs, which sometimes do not align with the common needs and challenges of the trans population more broadly and especially seem to overlook the needs of multiply marginalized trans people such as trans people of color.”

“How can these technologies help us survive in a world that’s increasingly hostile to trans people just existing?”

In doing so, he isn’t merely cataloging tech that trans people made. Nor is he merely suspicious of Big Tech power structures that exclude and marginalize. All that’s here, of course. But he’s advocating for something more fundamental: actively reimagining design processes to center the needs of communities most affected by design outcomes.

This shift feels particularly urgent given the current political landscape. “The big question that we need to think about now,” Haimson tells me, “is how can these technologies help us survive in a world that’s increasingly hostile to trans people just existing?” What’s critical now are technologies facilitating mutual aid networks and resistance tools. In documenting some of these systems, Haimson offers not just critique but blueprint. It’s a roadmap drawn not by venture capitalists but by those for whom innovation isn’t luxury but necessity.

Before Haimson logged on for our interview, I’d spent the prior weekend voraciously reading much of the book and knew I had a good problem for a writer and a bad problem for a busy interview subject: way too many questions. The book is a compelling compendium of trans technologies that defy easy categorization. I could spend an hour breaking down each entry, illuminating a different facet of what happens when marginalized communities build more habitable online worlds for ourselves.

Four examples we spoke about highlight what we need to see more of — and one, in particular, highlighted what not to do.

Example one: “Probably most people's first question when I tell them there's a trans banking app is why do we need a trans-specific bank?” Haimson asks with a hint of incredulity.

Bliss, part of the venture-backed Euphoria suite of apps, illustrates what Haimson defines as “trans capitalism,” the strategic commodification and monetization of trans identities. The banking app offers users cash-back rewards specifically earmarked for transition-related expenses rather than the typical points system found in conventional banking products. Users can save for surgeries, clothing, or other gender-affirming needs. The premise sounds supportive until you realize nobody in trans communities was clamoring for gender-affirming financial services. It’s an app that seems designed for trans people who have loads of money to spend, which isn’t most trans people. The app, partly funded by Chelsea Clinton, famously got “ratioed” on trans Twitter in 2021.

“It’s an example of a creator just deciding that something was a good idea based on her own thoughts and experiences, but not really taking much of a community-based approach,” Haimson explains. This individualistic approach to trans technology design typifies a recurring pattern identified throughout his research: solutions in search of problems, typically conceived by creators with relative privilege who haven't bothered to ask what the community actually needs.

The app joins other curious offerings that have struck a nerve with trans people on the internet — like Pronoun Water. Yes, branded water bottles displaying your pronouns.

What these commodified technologies and products ultimately reveal is the capitalist instinct to carve new consumer demographics out of marginalized identities. As Haimson put it, they're “something that people could buy, someone could make a little money, but not really something that's going to help the community in meaningful ways.”

Example two: In early 2022, game designer Sasha Winter fired off a tweet with a dark red and black graphic announcing the Trans Fucking Rage Jam in a Goth-looking font. The spontaneous digital gathering on indie game platform itch.io emerged as Winter processed her fury about Idaho's then-trending anti-trans legislation. What began as a personal outlet for political frustration quickly mushroomed into a collective howl. The itch.io jam had a gloriously straightforward creative directive in all caps: “MAKE IT LOUD MAKE IT ANGRY MAKE IT UGLY.” Game on.

“I was at work on a Tuesday night,” Winter told Haimson. “It was the night Idaho was trending because of that legislature that made it a crime to leave the state with a transgender child for whom you helped get gender-affirming care.” By morning, Winter's call had received more than a hundred retweets. The resulting Discord server soon housed 150 participants. The jam ultimately yielded 83 game submissions, all sharing the blood-and-shadow color palette that echoed the community’s mood.

But what makes this example particularly fascinating is what happened next. “A few months later I saw on her Twitter again that she was now hosting the Trans Joy Jam,” Haimson tells me. This follow-up featured pastel colors and gentle themes — like cats, fairies and self-care — created largely by the same community who’d previously channeled their rage. “It wasn’t like at the beginning of the year everyone was so angry, and then a few months later, everyone was suddenly filled with joy,” Haimson emphasizes. “Instead, it's that this is all existing together in each person.” If only dominant society could imagine that.

This simultaneity exemplifies what Haimson calls “ambivalence” — not indifference, but the complex experience of holding opposing emotions in productive tension. It’s a quintessentially trans experience: navigating a world that demands you choose sides while your lived reality transcends such binaries. In an online landscape that flattens nuance and rewards extremes, these paired game jams carved out space for something more authentic.

The Rage/Joy Jams demonstrate what happens when marginalized communities reclaim technological spaces to process their experiences collectively rather than in isolation. They represent what Haimson calls “technological trans care,” community-centered design that addresses genuine emotional needs without exploiting them.

Example three: “There’s rarely a relationship between having all this funding and being sustainable,” Haimson observes of the handful of venture-backed trans-owned startups. It cuts to the heart of what makes TRACE such a compelling case study in trans tech lifecycles.

TRACE was created by fitness star Aydian Dowling, that trans guy with abs you could bounce quarters off who landed on a Men's Health’s cover. It combined transition tracking features with social networking capabilities, allowing users to document their journeys while finding online community.

Unlike the questionable banking apps and pronoun water bottles littering the landscape of trans capitalism, TRACE actually did many things right, Haimson explains. Dowling leveraged his substantial social media following to build an active user base. The team conducted legitimate user research and incorporated community feedback into their design decisions. They created genuinely useful features like hormone injection reminders alongside spaces for users to connect about transition and trans life, in general.

“There’s rarely a relationship between having all this funding and being sustainable.”

Yet despite this textbook startup approach and attempts to secure funding, TRACE quietly shuttered after Haimson completed his research. “It wasn't incredibly clear why they decided to stop making the app,” he tells me, “but it sounded like it had something to do with not really being successful with investment funding.” The app joins countless other well-intentioned platforms in the digital graveyard. It’s a cautionary tale about the precarity of even thoughtfully designed technologies serving marginalized communities.

What TRACE ultimately reveals is the fundamental misalignment between conventional funding models and sustainable trans technologies. “I don't think the future that I want to see, at least, is in having millions of dollars from investment funding,” Haimson explains. “I think we need to find something in the middle there between people who are getting burnt out because they are doing this in their free time […] and people who have millions of dollars and are still not making it work.”

This middle path — moderate but sustainable funding, with a business model aligned with community needs and wants — remains stubbornly elusive for many tech creators.

Example four: “One thing that I try to emphasize in the book is about how thinking about technology in a trans way can actually change what we mean by technology and what technology can do,” Haimson tells me, before launching into the story of Probably Chelsea. It’s perhaps the most conceptually radical project featured in his research. When a magazine wanted to profile Chelsea Manning during her imprisonment, they faced a unique problem: no one had seen Manning post-transition, and prison officials weren't about to permit photoshoots.

Enter artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg, whose work with DNA phenotyping offered an unlikely solution. Manning sent hair clippings and cheek swabs from prison, which Dewey-Hagborg processed through computational systems to generate not one but multiple potential facial renderings based on Manning’s genetic material. The technological twist? The software allowed for gender expression as a sliding scale.

Video showing the Probably Chelsea project, from the artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg.

“There was a way that they could only choose to have either neutral or female interpretations of this DNA data,” Haimson explains. “So they made all of these different images.” The resulting series of 3D-printed masks presented dozens of possible Chelseas, a physical manifestation of identity as probability cloud rather than fixed point. Later, after Manning’s release, she stood face-to-face with these renderings in an exhibition.

What makes this project so compelling is how it reframes technology as a tool for agency rather than, say, surveillance. While facial recognition systems typically trap people in rigid identity categories, Probably Chelsea reimagines technology to expand possibilities, thus practicing trans tech care. The project stands as testament to what happens when technologies designed to catalog and constrain human variation get repurposed by the very people they were meant to classify.

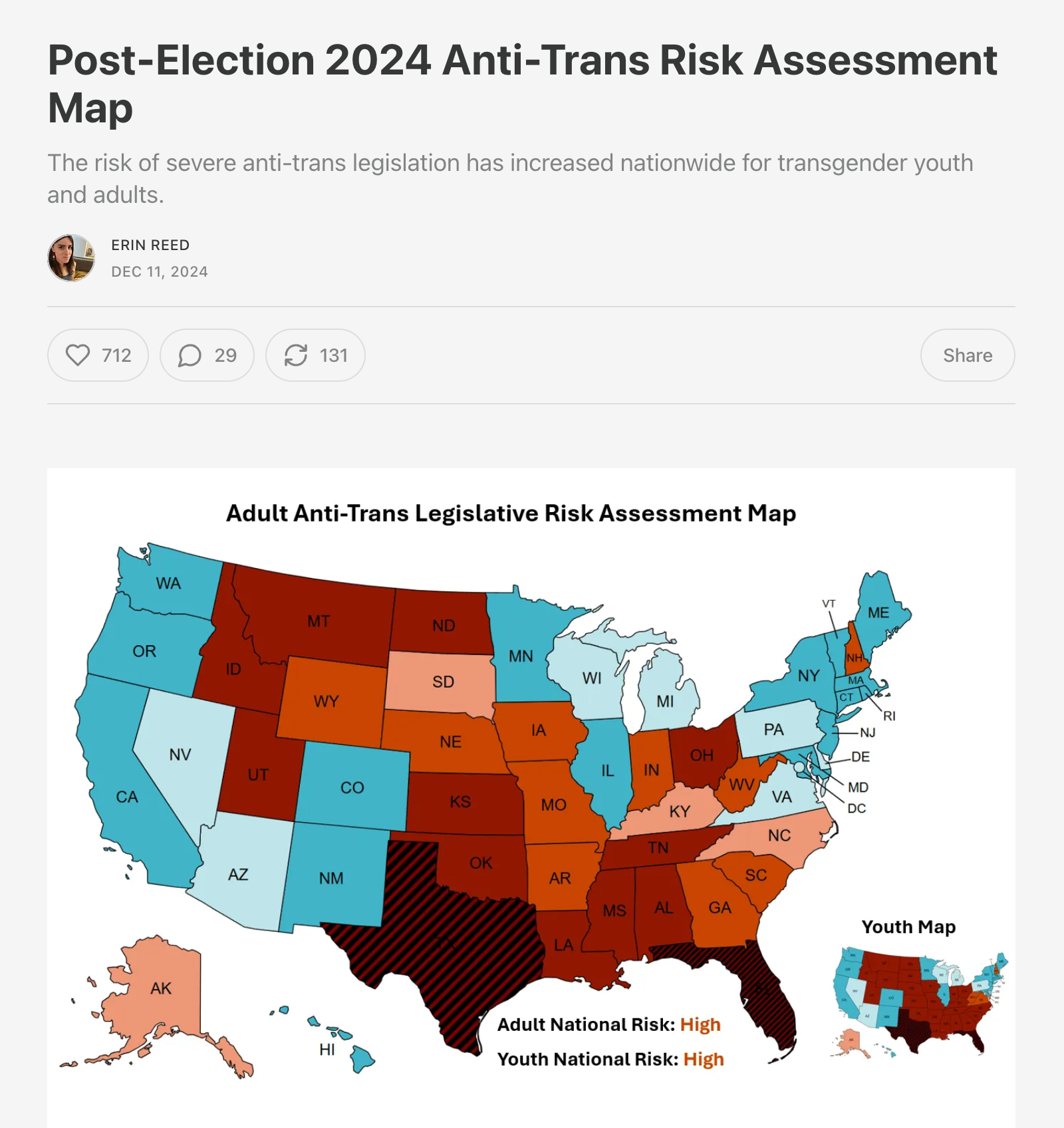

Example five: “It feels very much like a classic fascist tactic of overwhelming a marginalized target with so much noise,” I observe about, well, gestures at everything during our conversation. Haimson nods emphatically. We're discussing the context to Erin Reed’s Anti-Trans Legislative Risk Map, a color-coded geography of American fascism that has become essential survival infrastructure for trans people navigating an increasingly balkanized and hostile landscape.

Reed, a leading trans activist and journalist covering the far-right assault on trans rights, created the resource out of community necessity. Her earlier project, a map of informed consent healthcare providers, demonstrated her talent for transforming overwhelming information into navigable terrain. But as state legislatures expanded their coordinated attacks, Reed recognized the urgency of creating an essential kind of cartography. Now she reads every anti-trans bill — 550 bills in 2023 and 586 in 2024 — and uses social media and her newsletter to reach audiences who desperately need this information for their personal safety. Reed represents the overlap of ethical journalism, information activism and trans-ing platforms.

“This is a really important way of responding to the current moment, when there’s so much chaos and confusion,” Haimson explains, “because we didn’t have someone analyzing [all the legislation] until Erin did that.” The resulting visualization and guide has become a critical resource that transforms abstract legal threats into, well, truly actionable insights. Florida and Texas’ deep red “do not travel” warning speaks for itself.

Reed’s map responds directly to the material conditions of trans existence. It helps families decide where vacations are safe, job-seekers identify states where they won't risk criminalization and communities coordinate resources where they're most needed. “That's something that's really working towards actual needs that people have,” Haimson emphasizes. Reed's map performs the essential political act of cutting through chaos to reveal the pattern — transforming noise into signal for a community under siege.

“When you think about the contrast between that and Pronoun Water, well, you know what I mean. Like, [Reed’s map] is just really addressing things that matter.”

I first spoke with Haimson for a feature I wrote in Them in 2022, following two weeks of reporting on Elon Musk’s chaotic takeover of Twitter and the platform’s far-right death spiral. We spoke about his 2021 study about content removals on social media and who is really affected most by censorship, despite conservative’s whining about “free speech absolutism.” You guessed it: “Trans and Black participants were more likely to experience disproportionate content removal even when the content they posted followed the site’s guidelines. These groups are also more likely to experience harassment on those same platforms.”

In many ways, what was happening to FKA Twitter then is now happening to America’s democracy, with the targeting of those most marginalized in society. Once again, trans tech creators are responding to the moment.

That was the context for a conversation ranging from the need to urgently focus on trans survival to why Haimson thinks we need to hit, well, the escape key on the way tech is currently designed.

To be sure, we did not in this interview endeavor to solve the techno-capitalist dystopia of modern love, as Faye accurately defined it last week at London’s Southbank Centre. But from his home in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Haimson did send me this photo of him and his infinitely loving dog, Rufus Joon, as a little moment of joy to balance out the timely rage.

I’ll start with a somewhat meta question given I’m supposed to be the interviewer: What do you think is the most important question we should be asking about trans technologies right now?

In the book, I argue quite a bit that we need to start by understanding what the needs are. It’s so clear in this moment that people need to survive in this world that is increasingly hostile to trans people. So the big question we need to think about now is how can these technologies help us survive in a world that’s increasingly hostile to trans people just existing?

I want us to focus on the needs that are most dire. That’s probably not being able to track our HRT and get a reminder when to take our shot. That’s important, and I'm glad we have apps that do that, but what we really need is technology that helps us stay alive. Recently, I think a lot of that is around mutual aid and finding ways to connect people who can offer support with people who really need it.

There are practical things like that, but people also need things that give them hope — and that often comes through games, art and creative mechanisms. Obviously, art isn’t going to solve the political crisis, but these creative outlets are really important on a personal level to keep people going and provide motivation when things feel hopeless.

Talking to more than 100 creators of technology takes a long time. In fact, it took you a year. What was the most surprising thing you found in that year of many conversations?

It was the scope of trans technologies. I went into this thinking it wasn't that long of a list. I thought I was going to be able to reach out to everybody who was creating trans technology. [laughs]

But not only did I learn about a bunch of technologies I never would have thought of, throughout that year there were people who were starting up new trans technologies who didn't even have those technical skills at the beginning of the year when I started this study.

Things were just exploding in a way that I wasn't predicting at all. That was really exciting, but at some point I had to say, “I have to stop doing interviews.” [laughs] I thought at first that I could cover the entire space, but it wasn’t possible.

Take the Trans Fucking Rage Jam, for example. There were about 85 entries to that, and each of those creators could have been an interview in my study, but that happened towards the end of my data collection.

That was very surprising to me, just how big the space is. And it’s way bigger now, even.

“I study technology to learn more about transness, and trans identity to understand more about technology.”

You define your mission statement in a beautifully simple way: “I study technology to learn more about transness, and trans identity to understand more about technology.” Beyond the fact of exclusion and marginalization, what do trans technologies tell us about dominant tech narratives?

It’s really interesting to think about what happens after we are left out of dominant technological platforms.

For the first five or so years of my career as a researcher, I was really trying to understand how we can make these mainstream platforms more inclusive and how to work with Facebook, for instance, to make sure they include trans people.

Now we know that Meta never really cared. It felt performative the whole time when they were talking about inclusion. I mean, I was always resistant to working with Facebook or Meta, but now it's clear they just never really cared.

There is some power in trying to make existing platforms better, but what's more powerful is building our own platforms and thinking outside these mainstream tech spaces.

When trans people and other marginalized groups are excluded from dominant platforms, it’s frustrating. But that exclusion sparks creativity that leads to these exciting new worlds that don't exist in the mainstream tech industry — and kind of couldn’t exist there because they're not connected with Big Tech money.

It opens up new ways of thinking about technology. And that’s not just for trans people — it’s any group or identity that’s trying to use mainstream platforms and just can’t for whatever reason.

In my research group, we’re calling this “community-built online communities,” and that’s something we’re hoping to work on more in the future. I'm not interested anymore in asking how Meta can be more inclusive. They just don't care.

“I'm not interested anymore in asking how Meta can be more inclusive. They just don't care.”

The book opens with your experience trying to find surgery resources in 2010. You write: “The only tool that I had was Google search — and that was how I found the surgeon who botched my first top surgery. The trans technologies I discuss in this book are actively helping many trans people, and I wish they had been available to me early in my transition and to others who needed them before they existed.” How different would that journey be today with current trans technologies?

A lot has changed. Specifically for my own experience, there's a site now called Mod Club that is for trans masculine people and trans men to build community, share photos of surgeries and things like that. That was exactly what I needed at the time, and I wasn't able to access those types of resources mostly because they didn’t exist. Yes, there was Transbucket, but they did a lot of vetting before letting people in, which is obviously needed and a good thing, but I was essentially vetted out at the time.

I would have benefited from understanding the range of what these surgeries can look like and being able to talk with people about their experiences. As I mentioned in the book, I was in community with trans and queer people, but there weren’t many people I knew who had gone through this same experience. I had really limited information.

That’s what people need now — more information. There are a lot more surgeons out there now, so many people can actually go local, especially for something like top surgery. But even with this increase, people need to see photos and talk with patients of those surgeons to make informed decisions.

What’s interesting is that it wasn’t as politicized back when I transitioned. Even though there were fewer surgeons and it wasn't covered by many insurance plans, nowadays it's so heavily politicized that people need support even more.

A lot of that support happens in these tech-mediated spaces because it's unlikely you’ll have people in your physical location who are having the same experience. Often they’re near you physically — you just wouldn't know them. Locally in Ann Arbor, there's a Facebook group for one surgeon who does top surgery here, and people join that group just to hear about others’ experiences. Something like that definitely didn't exist back in 2010.

We still have the question of how to vet people for these spaces. You don’t want to exclude people who aren't “trans enough” or haven't started transition yet. But it’s really hard to know where to draw the line between keeping out potentially harmful people versus accidentally excluding people who maybe aren’t sure if they’re going to transition but really still need that information.

You write about how trans technologies often start from personal needs but can accidentally reproduce privilege. What would more inclusive trans tech design look like? What’s the deeper lesson here about design more broadly?

A lot of this is in the design justice framework — basically being connected with communities, making sure those communities are involved in design processes, and starting from a place of gathering information rather than just going in and building something right away.

If you just jump into building mode, you're really just drawing from your own experiences or maybe people you know personally. That's going to exclude a lot of people, and often the people it’s excluding are multiply marginalized trans people.

The people who are more likely to have technical skills, resources and the ability to create technologies are going to be the more privileged people in the trans community. That’s why we see so many cases where tech ends up reproducing privilege.

It’s not enough that it’s just a trans person creating the technology — it needs to be based in community. Really starting with information gathering and connecting to people who are different from the creator themselves.

“We need to press the escape key on the way things are designed in mainstream platforms.”

In reading your work, there’s an irony I spot here at the heart of it: the folks most marginalized by mainstream tech might have the most helpful perspectives on how we fix what’s broken. That’s because surviving at the margins requires developing the kind of critical and creative approaches we desperately need right now. That seems central to the idea of transing tech — not just making better tech for trans people, but fundamentally changing what technology can be. What happens when we apply that lens to technology broadly?

It’s kind of like what you say about the concept for ESC KEY — we need to press the escape key on the way things are designed in mainstream platforms.

Tech designers are often thinking about this so-called “average user.” How can we make something that works for an average user? But the reality is there is no average user — that doesn't actually exist. I truly believe that every person has some sort of stigma, some sort of marginalization or some way they need to use technology in unique and personal ways that aren't going to be “average.”

We need to move away from thinking about design in that way entirely and instead think about flexibility. But that's not even enough. In the book I talk about “plasticity,” which is a bit more complicated and theoretical.

In transing tech, the way I'm conceptualizing it, we’re trying to turn technology into something new and different that works for people who have complex identities, people whose identities are changing. And that's not only trans people — that’s everybody. Everybody goes through life transitions. Everybody is complex in ways that even people in their life would not know. We need technologies that understand that and can work even if your identity today is very different from what it was a few months ago.

There's a lot of value in creating technologies that are specific for marginalized groups. But at the same time, we could technically “trans” any technology and make it work better for the ways that people’s lives and identities actually are.

In this current moment of heightened anti-trans legislation and attacks from many directions, what role do you see technology playing in community support and survival?

At the current moment, people are stunned, confused and distressed. Soon we'll see people turning that frustration into creative tech design — but I think people aren’t quite there yet.

When I saw the response to the initial set of anti-trans laws in 2021 and 2022, there were so many efforts that emerged. It does take a little time to get there.

There are things happening right now, mostly with people who already had systems set up. I've seen streamers doing mutual aid streams for people who need help, people collecting and distributing information through resource sites and, of course, Trans Lifeline maintaining that vital resource that helps keep everyone alive during this time.

We're going to see a lot more people responding with exciting and creative technologies that come from that place of rage and frustration. I’m excited to see what happens next because I don’t think people are going to just sit here and take what's coming at us. People are going to rise up, and those who are excited about technology and have the skills to create it are going to come up with some really cool new things that will actually help us.

The book ends with some fascinating thoughts about “trans technological futures,” which, yes, I admit, is fun to say. What gives you hope?

I feel really hopeful when I think about, say, these teenagers creating browser extensions in their bedrooms. There was one person’s email I quoted [at the start of the final chapter] who I couldn’t interview because they were only 16 years old — I needed participants to be 18 for my research.

There are so many young people using technology as a form of resistance, and that’s super important. They're going to think of things that I wouldn't think of in a million years. I really can’t wait to see what they do next.

Is there anything else we didn't cover in this interview that you think is just really important to say about your book aside from “buy it”?

Well, it will actually be free to access, so you don't even have to buy it.

You’re right — I already knew that. (Download it here, folks.)

I've edited and condensed my conversation with Haimson for clarity.

“Trans Technologies” is available now via MIT Press.