The state of nightlife: No-phone clubs? Brand mascots in the DJ booth? Who can afford to resist?!

The British nightlife trade group recently announced all the clubs could close by 2030 without urgent action. ESC KEY .CO speaks with longtime music journalist and cultural insights agency founder Andy Crysell about his new book, “Selling the Night,” and the big forces reshaping club culture today.

Suspend disbelief. Get in the time machine. Turn the dial back about 18 centuries to meet Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, who ruled Rome for a mere four years, better known by the posthumous nicknames Heliogabalus or Elagabalus. At 18, Elagabalus was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard — stripped naked alongside their mother, their bodies dragged through streets, their face chiseled off statues and replaced with the next emperor’s. This is termed damnatio memoriae in Latin. Total erasure.

What could provoke such vengeance? Among other transgressions: throwing some truly infamous parties.

In the millennia since, Elagabalus has become synonymous with hedonism, an aesthetic anti-hero for numerous artists such as those in the 19th century Decadent movement.

The 1888 painting “The Roses of Heliogabalus” by Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicts one legendary banquet — guests drowning in an ocean of pink rose petals released from a false ceiling. Overdramatized? Most certainly. But I'd argue it's exactly the kind of party you'd invent a time machine to attend.

At this superficial level, the story of Elagabalus becomes a strained metaphor for club culture today: one day you’re throwing wild parties to some new god, the next the no-fun cops show up and the heads of all your lovers roll.

Have we focused on maximizing productivity and over-optimizing every corner of our lives that we can’t embrace a little messy hedonism? Does it sometimes feel like the emperor of the night has been assassinated? How many of our sacred spaces dedicated to the after-dark arts have been defiled, defaced and condemned to build new condos — damnatio memoriae but for club culture?

Three months ago, I didn’t know how to pronounce Elagabalus.

More recently, Elagabalus has become an icon for at least a few queer and trans nightlife creators, who see some elements of our own communities’ experience reflected in Elagabalus’s story.

But, frankly, I knew nothing about Elagabalus, their lovers or the 19th century oil painting until February. That’s when I stepped into East London’s latest queer space: named, yes, Roses of Elagabalus.

That’s because another part of their tragedy is, of course, Elagabalus’s marginalized sexuality and gender, which are subjects of speculation and fascination among historians. A man thought to be Elagabalus’s lover and sometimes described as their husband was the charioteer Hierocles. (Relatedly, charioteer is a very butch coded job.) He was executed after Elagabalus’s assassination.

The historical record is contested, as much of what was written about their reign comes from hostile contemporary sources (apparently, Senator Lucius Cassius Dio did not get down with Elagabalus and wrote some potentially skewed accounts of the emperor’s times). Some records suggest that Elagabalus preferred to be referred to as a lady rather than a lord, wearing makeup and wigs. Viewed through a modern lens, you might say they were the trans and queer emperor of Rome.

“Does it sometimes feel like the emperor of the night has been assassinated?”

Filled with lavish drapes and mirrors, the Dalston spot named for them has quickly become a word-of-mouth hit. The bi-level space contains a spendy-but-sexy cocktail lounge, cabaret shows and a compact DJ space. It’s undeniably plush, a little art deco and decidedly camp. “Visually the gayest place I have ever seen ... like if David Lynch was a lesbian,” one early Google reviewer wrote of the brand new venue on Kingsland Road. And as strange as that description sounds, I get it (the textures throughout serve a little “Twin Peaks: The Return” energy).

I first learned Elagabalus was an emperor by glancing at the cocktail menu, where a description of the narrow club’s concept draws a link to the obscure chapter of Roman history. I thought, cool, what curious queer ephemera! I pulled out my phone to take a photo, instantly reminded that the host at the door had placed a strip of green tape over the camera bump. (“A queer who married a vestal virgin, a trans woman who searched the empire for the biggest cock of all; Elegabalus became a cautionary tale for Roman historians, an inspiration for the fin de siècle aesthetes and a muse to us at The Roses,” the proprietors write of their concept.)

That’s why there are hardly any photos of the space online — which, in this era of visual overload, is unusual and refreshing.

The Roses of Elagabalus is far from the first nightlife spot to ban phones and photography. But it’s an example of how these policies have trickled down from the capitals of techno tourism into more intimate spaces. Such policies first began in Berlin’s queer party scene as well as at venues such as Tresor, UFO, Planet, Snax Club and eventually Berghain, later arriving to London clubs like FOLD and Fabric, Andy Crysell documents in his sprawling new book, “Selling the Night: When Club Culture Meets Brands, Advertising and the Creative Industries,” which came out on Friday from Velocity Press.

The result of nine months of research, it’s a compelling and balanced survey that maps a range of perspectives on the commercial and cultural impacts of club culture. Crysell traces influences from fashion and interior design through to cheap easyJet flights’ role in globalizing dance music and that awkward fast food intrusion into corporatized festivals. Through it all, Crysell resists easy narratives. He goes deep into curious anecdotes with key figures in 20th and 21st century club culture. He loops in the voices of practitioners on the agency and brand sides, too. And generously cites academics, archivists, activists, policymakers, photographers, writers and designers.

“The sight of clubbers who are not joyously waving their arms in the air but instead holding their phones aloft.”

The book dances around nuances like how nightlife is simultaneously framed as the antidote to our very logged on era and yet victim to it. Does anyone need to see another smartphone video clip of a DJ bro mid-drop, Crysell asks rhetorically? “Anyone interested in club culture has probably seen one of the videos on X, TikTok and similar, mocking the sight of clubbers who are not joyously waving their arms in the air but instead using them to hold their phones aloft,” he writes. “’No phones on the dancefloor’ has increasingly been the response.”

Many clubs enforce such policies with stickers and, yes, tape. It partly stems from a sense of privacy and community protection, especially timely in LGBTQ+ spaces during a time of rising hatred and violence. It’s also an attempt to rekindle the hedonism and escapism that some feel we’ve lost in contemporary nightlife, a rich creative ecosystem that’s viewed by many on the inside as vulnerable and in need of urgent action.

It also speaks to a collective view that something is broken about the ways we gather in social spaces after dark, the ways we’re not present in the moment, the very online ways in which we party “IRL.”

Everyone seems to agree something big is wrong. But who’s to blame and who should fix it are matters of fierce debate in nightlife spaces at present.

Technology is an obvious, perhaps too easy, culprit for all that ails nightlife. Certainly, the sentiment — or “insight,” as cultural strategists might say — has reached the big glossy desks of the C-suite.

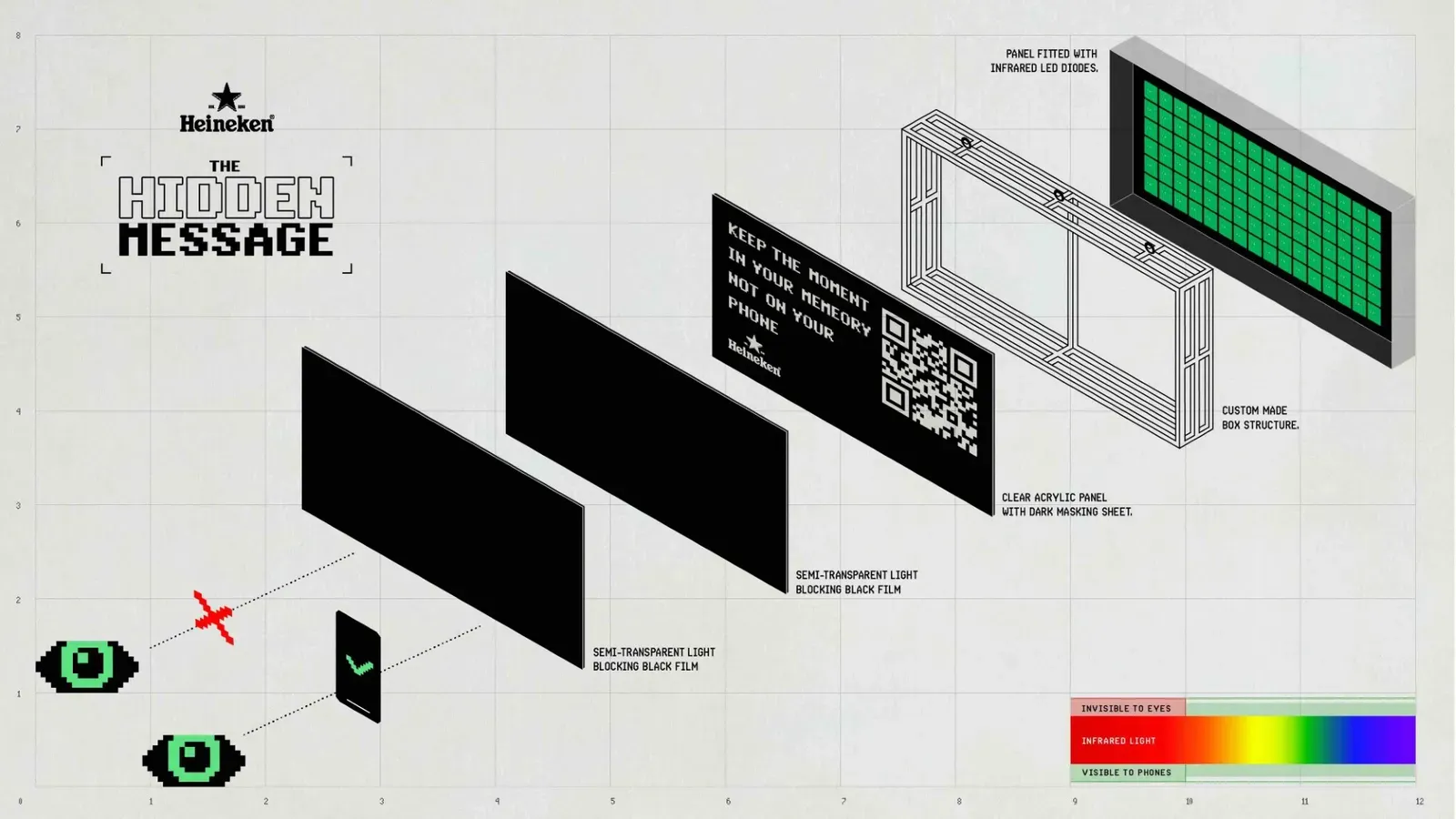

For instance, if attendees at October’s Amsterdam Dance Event opened their phone’s camera to film Scottish DJ Barry Can’t Swim’s set, they’d see an infrared light message on their screen, which was otherwise invisible to the eye. The message prompted them not to film the set and advertised a free app, The Boring Mode. Once downloaded and enabled, it can block all other apps, notifications and the camera for a set period of time.

The infrared light display and app were a clever promotional stunt by Heineken. Aesthetically, the Boring Mode app makes a touch-screen smart phone resemble a keypad “dumbphone” (formerly known as a “phone”). It follows another hyped collaboration last year between the Dutch beer brand, Human Mobile Devices and streetwear store Bodega. Dubbed the Boring Phone, the limited-edition flip device promised better nights out by liberating attendees from distractions. (I want one, too.)

Agencies LePub Milan and LePub Mexico City created this hidden message campaign for Heineken, promoting The Boring Mode app.

It’s also slightly ironic given that another complaint about the state of nightlife happens to be the overtly promotional presence of brands at the parities, which has for decades been seen by some brands as a fast lane to cultural relevance. And a smart one at that. But it’s also a road fraught with potential reputation risks for all parties involved. Brands don’t want to be seen as co-opting the culture. Nightlife organizers don’t want to be seen as selling out.

“My view is there's something different about creativity that’s formed in the night. There’s an urgency, a necessity to it. Potentially, it could be quite democratizing,” Crysell tells me. But, on the flip side, there’s now a sense from some the best of nightlife is in the past, a point made in part by the mere fact that club culture has been the topic of many museum exhibitions, gallery shows, the subject of historical dissertations and documentaries, and even book clubs have formed that tend to speak about going out in the past tense.

“There's the festival-ization of dance music. The gentrification of dance music. The museumification of it. The academification and intellectualization of it. It can feel like people are more interested in dance music in every way other than actually dancing in clubs anymore,” Crysell tells ESC KEY .CO in the full interview below.

It might make you wonder, “Is nightlife dead?” It’s one of those “I’d be a millionaire if I got a quid every time somebody asks …” kinds of questions. But Crysell’s book makes clear it’s the wrong question to ask.

For every headline about the existential threat to club culture, you can also find examples of young DJs rekindling raving in second cities, new venues and parties inspiring hope, and the digital detox of a taped phone reeducating some of us on how to be present. Club culture isn’t dead, but its sustainability is at risk. The parts of it that seem particularly at risk are what many of us value clubbing for the most: the sense of community, the grassroots, the hustling do-it-yourself underground, the creative counterculture where anyone with determination can make a splash without, say, the backing of millionaire parents. In cities like London or New York, it now feels like you need millionaire parents.

In other words, the state of nightlife is fraught with tension. Therefore, one central thread running through Crysell’s survey of nightlife today is between more intentional community-centered movements (think recurring parties, DJ collectives, small venues focused on marginalized revelers) and the corporatization of dance music (seen at, say, major EDM festivals where the vibes feel detached from the radical DIY roots).

“Brands don’t want to be seen as co-opting the culture. Nightlife organizers don’t want to be seen as selling out.”

In April 2019, dance music hit peak corporate absurdity when a DJ wearing a massive Colonel Sanders helmet — yes, the KFC mascot — took the stage at Miami’s Ultra Music Festival for a surreal five-minute set. The fast-food icon blasted EDM while screens displayed giant Colonels with heart-eyes, tweeting afterward about being “a huge fan of electronic music for the last few days.” The stunt provoked immediate backlash online. “What level of capitalism is this?” asked one commenter. Music publications were predictably merciless. Pitchfork declared “a line finally may have been crossed,” suggesting the spectacle represented the “general spiritual decay” of an industry where product placement had finally supplanted the music itself.

This is the bottom-of-the-barrel anecdote that the book rightly opens with as a cautionary tale.

“When you look at the creative industries and you look at it in honesty, it really is about a handful of very large corporations now that rule it. The money is not being evenly distributed. It is tending to create very monocultural outputs,” Crysell tells me.

“So maybe club culture shouldn't think of itself as being such a strong part of that world?” he summarizes the question on the mind in a lot of contemporary subculture spaces. In attempting to answer those kinds of questions, he ends up becoming a historian of nightlife.

He tracks two primary “directions of travel” — “brands moving into club culture and the ideas and people that have organically emerged from nightlife into the wider creative industries.” Clearly, the first direction raises a lot of concerns about big words with ever-shifting definitions like “authenticity” and “community.” But feeling the crunch from rampant gentrification and ambivalent government policies, who can afford to resist?

It’s impossible to talk about the state of nightlife without talking about the state of our cities. The United Kingdom could be a canary in the coal mine. By some estimates, club culture is on the “brink of extinction” here. The trade membership group Night Time Industries Association (NTIA) has predicted when Brits can enjoy their last night out: December 31, 2029. That’ll be the end of an era, where clubs have vanished completely. That is, if the current rate of closures continues.

The argument goes that the United Kingdom, a global hub of rave culture, which emerged as an underground cultural force in the ’90s, has abandoned its nighttime economy. “The current trajectory spells disaster not only for the businesses themselves but for the communities they serve,” said Sacha Lord, former night time economy advisor for Greater Manchester, in a press release supporting the NTIA campaign in September. “We cannot afford to lose these spaces — they are the lifeblood of our cities.”

“By some estimates, club culture is on the ‘brink of extinction.’”

Between March 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and September 2024, the United Kingdom has lost 37% of its clubs, NTIA says. That’s three clubs lost per week. By that rate, they’ll all be gone by the dawn of the coming decade.

“The Last Night Out,” the McCann London-created campaign, promotes British voters to sign a petition and contact their Members of Parliament. The petition calls for financial support for the industry; cultural protection for clubs, akin to the status of galleries and museums; and widespread reforms to regulations, taxes and planning policies that make operating a club increasingly expensive and opening a new one even harder.

Case in point: In London, as in other major global cities, it seems every month brings news of a beloved venue organizing a campaign to try and save itself from closure along with another announcing they’ve shut down for good. “Without being able to make noise, we can’t make money,” Edie Kench-Andrews, general manager of Hackney’s MOTH Club, told the BBC in January, as the independent music venue is under threat due to proposed condo development. A few minutes’ walk away from MOTH Club, the beloved boozer and underground DJ pub The Gun closed its doors last month. Hackney, the center of East London’s gentrification, has become a victim of its own nightlife success. The very thing that has made it one of the most popular places to live among the so-called “creative class,” in Richard Florida’s terminology, has also helped accelerate its own demise.

It’s a familiar narrative in places that get deemed “cool.” Creative types move in because it’s comparatively cheap, driving out original residents in the process. They open cool spaces that become cultural hubs that lure people who, at first, refer to it using the euphemism “up-and-coming” neighborhood. But then the newcomer NIMBYs inevitably complain about noise. Rents rise. All other costs skyrocket. Then the venues close. The cycle repeats somewhere euphemistically dubbed a bit more “raw” in contrast.

Some cities appoint night mayors, who handle competing demands from public safety, club owners, event organizers and, of course, whiny residents who move into a “cool” area and then decide they hate anyone else having fun. But gentrification roars along, unperturbed.

In “Selling the Night,” Crysell cites Michael Kill, CEO of NTIA, speaking in 2023: “The closure of nightclubs transcends mere economic repercussions,” Kill said then. “It represents a cultural crisis endangering the vibrancy and diversity of our nightlife. Nightclubs serve as vital hubs of social interaction, artistic expression and community cohesion, making their preservation imperative.”

Understandably then, themes of gentrification, policy neglect, wealth and class, nepotism and gatekeeping are central in understanding the bad vibes around nightlife at the moment. These undercurrents ripple through every chapter in Crysell’s book, too.

“Predictably, the threats to night culture and its economy cannot be put down to one thing. Next to rising costs, there’s the lasting impact of the pandemic – including a switching off from IRL experiences that some have found hard to switch back on. A preference for fewer, bigger nights out, with this particularly impacting midweek clubs,” Crysell writes in the seventh chapter, noting that spending on nightlife was generally down in the years following the pandemic. “So much for the heavily touted Roaring Twenties to follow in the wake of the pandemic shutdown.”

“Is there a way forward without a fast food mascot showing up as an unstoppable ad in the DJ booth?”

And yet, the fascination with nightlife’s transformative power persists in post-pandemic pop culture, perhaps most visibly Beyoncé’s 2022 album “Renaissance” was a tribute to the Black and LGBTQ+ roots of dance music. Even 2024’s Brat summer thrust club culture aesthetics into U.S. politics — a further pop tribute to the cultural resonance of the underground. And most recently, FKA twigs has credited her 2025 album, “Eusexua,” to a euphoric moment of clarity she experienced while dancing to techno in Prague. In March, twigs headlined two sold-out London shows at Magazine, a venue on the banks of the Thames in North Greenwich.

Everyone wants to celebrate the culture, clearly, but is there a way to fund it without a fast food mascot showing up as an unstoppable ad in the DJ booth?

Amid the disheartening statistics a quiet revolution bubbles beneath the surface. But it seems to be more readily embraced in some communities than in others, leaving the state of nightlife a tad more full of life in, say, the queerer corners.

Part of this speaks to the different reasons people rave. For some, it’s merely escape. For others, it’s one of the few ways we build and maintain a sense of community amid a dominant culture that’s hostile to us. Even as gay bars struggle to stay alive, there are promising undercurrents in London’s queer club scene today — revolving around monthly raves, day and night, that all emphasize the importance of creating space for marginalized people, for protecting community and rekindling something of rave’s radical roots. One popular LGBTQ+ rave at present, Howl, is both a “sexual wellness” brand selling, well, lube and an organizer of some big Hackney parties that bring back the dark room. It shows the blurring of lines between brand and party organizer.

“The level of resistance that's out there, the level of thinking of other ways of doing things, I found that really positive despite all the relentless negativity we tend to hear about the state of club culture and after-dark life these days,” Crysell tells me, pointing to a shift toward more intentional community-building.

This intentionality has manifested in collectives like Pxssy Palace, which organizers say celebrates “Black, Indigenous and people of color who are women, queer, intersex, trans or non-binary.” They’ve reimagined London’s nightlife experience by focusing on practical community needs including taxi funds for those who can't easily afford safe trips home and daytime party alternatives.

“What do hangovers give you? Anxiety. And the world is much more anxiety-inducing than it used to be.”

“For one, it's harder to get home at night. It's more expensive,” co-founder Nadine Artois told Vice in 2023. "But the main reason is people don't want to get totally legless. They want to savor the next day. [...] What does drinking and hangovers give you? Anxiety. And the world is much more anxiety-inducing than it used to be.”

More importantly, these collectives have mastered the delicate dance with brands without compromising their values. As Tom Dodd of WME explains in “Selling the Night,” Pxssy Palace maintains firm boundaries: “They're saying, ‘This is ours. If you want, you can help pay for it, but you're not going to be all over it. And you're not going to have a say about what we do or how we dress or what we look like.’” This approach protects sacred spaces while still securing vital funding. (After half a decade at the Hackney Wick venue Colour Factory, Pxssy Palace held an event in February, “The Last Dance,” and announced “stepping away from bigger themed parties,” with plans to unveil “what comes next” for the 10th anniversary in November.)

Despite these tensions, when brands do engage respectfully, meaningful partnerships can emerge. The Red Bull Music Academy, which ran for 21 years until 2019, stands as perhaps the gold standard, by Crysell’s measure — supporting educational initiatives and archival work while keeping its branding relatively subtle. Today's collectives aren't waiting for corporate saviors, though.

“Within dance music now, there's this sense that you can't just lead things to chance,” Crysell observes. “You have to arm yourself with tools and resources and support networks, and you have to educate. All of these things have to be done now if you want to start any chance of keeping subcultures alive.”

Crysell's own biography maps neatly to the directions of travel he tracks in the book, as someone who entered the creative industries through the “tradesmen's entrance,” as he put it in our interview, rather than the front door.

“I had a job as a foot messenger back when that was actually a thing,” Crysell tells me. “I used to deliver photos from a photographic company to ad agencies in London and around Soho. Literally, a job that would involve someone just sending a WeTransfer file these days.” The physical act of navigating these spaces opened his mind to the prospects of a career in the creative industries. “I was getting this exposure to what’s going on in ad agencies and so forth. But I never felt like I was going to get a job there.”

Then came acid house. “It changed everything for me, really,” he reflects. Having left school at 16 with no intention of going to university — “none of my family had either” — club culture offered what formal education couldn't: “a builder of confidence, a shower of bigger horizons, a way to connect with people.”

This led to a decade as a music journalist before pivoting to founding two agencies, giving him that rare sympathetic eye for both the underground's authenticity concerns and the commercial realities brands navigate. I first encountered Crysell through consulting on cultural strategy projects with his agency Crowd DNA — the consultancy he founded in 2008 and grew across continents before its acquisition by Strat7 Group in 2020.

Thus, his book delivers something that rejects the easy dystopian framing, tracing commercial and cultural threads from Harlem’s Pepsi clubs through Studio 54’s Fiorucci connection to today’s big branded festivals.

As the industry at large necessarily raises alarms about the risks to venues, grassroots efforts suggest that nightlife is still, ultimately, about people taking the initiative to bring other likeminded people together. It’s adapting despite the threats. It’s becoming more intentional, more inclusive and, at times, more exclusive for the people and subculture that deserve spaces to get lost in the music — maybe even, I don't know, a sea of rose petals released from a false ceiling?

I’m about to use some heavy finger quotes around the word trend here. It’s the sense that IRL feels like a “trend,” a novelty all of a sudden. It seems to speak to different macro-level forces post-lockdowns, and this sickness of our time: the widespread need for a “detox” from devices, for instance, which were pitched to us as tools but now we can’t really untether ourselves from. Recently, that has led to this revived interest in raves and what some have termed “soft clubbing” as a way of logging off and finding community. But the fact that we’re calling offline experiences “IRL” in the first place seems, well, bad. What do you think has fundamentally changed about how we understand presence, especially creativity after dark?

I guess it’s just not a given anymore, is it? It used to be a given. Now it's something you actively choose to do as a default from the norm being digital. I think you're absolutely correct that the fact we call it IRL and we've had to badge it and put it in that space is quite unsettling, really.

The positive way to think about it is, are we at the beginning of some kind of redress here? Are we going to return to people acknowledging that they want to do more things in person? The alarming way to think about it is that this is another trend in the cycle — a brief moment of IRLness before we head off and do some non-IRL things. The fact that doing things in person has been consigned to being the sideshow, even the novelty act, is certainly concerning.

When you look at what's happened to club culture, there's a bunch of things going on at once. Obviously, we are so absorbed by all things digital. But alongside that, there's the cost of living crisis, fear of safety at night, and people going out less often but to bigger events. People go to festivals or to Drumsheds once a quarter and spend a vast amount of money, but they don't go out on a Wednesday night to a small club in a basement. And gentrification is always in there — whatever the conversation is, it raises its head.

Back in the day, if you wanted to be part of club culture, you went to a club. There were fanzines and some pirate radio, but there was a scarcity of information and access. If you wanted to belong, you were there in congregation with others.

Nowadays, there's a convenient approximation of club culture via online platforms and endless recordings of DJ mixes and Boiler Room-type stuff. All of that has clearly had an impact on how people perceive that world.

“If you wanted to be part of club culture, you went to a club.”

I’m going to do something I’ve never done before and tell you the lede for this article before I write it: I popped into a newish venue in Dalston recently. First thing they did was put green masking tape over my iPhone camera. I was like, "Hey, I like this." There are hardly any photos of the venue online. Perfect. It seems to reflect this widespread sense that our devices have further alienated us from each other and invaded our privacy and intimacy. You've touched on that in your research — the rise of social media, mobile phones, that backlash rippling across nightlife. You write about how some of the most photographed clubs are now actively preventing photography. Is the phone-taping moment simply nostalgia, or does it represent a deeper resistance to content creator culture?

Like the IRL theme — is IRL logic kicking back in, or is it a brief novelty? Is that the same thing with phone taping as well?

I'm a little bit conflicted. I would love to think we should be able to behave ourselves and moderate our behaviors. If we want to take a couple of pictures of our mates in a club, then why shouldn't we? But sadly, we don't seem to be able to control ourselves. The dopamine hit won’t seem to allow many of us to do these things in moderation.

There are lots of arguments around why people should be allowed to self-express themselves. If they want to stay out of sight, if they want to stay hidden in a subculture and don't want that shared, then I think they have that right. So banning phones is a good thing. The impact of peer pressure is real — when one person films some spectacular drop, everyone has to get their phone out at once, and it is a sea of phones.

In a way, the big clubs get the behavior they deserve. It's the big clubs where you see most of the people getting their phones out, and maybe those clubs deserve it a little bit for the culture they create. But it's interesting when the smaller, more credible venues start doing it as well. It's indicative of how we're feeling troubled and conflicted at the moment. Whether it's the answer or not, I'm not really sure if sticking bits of tape over people's phones is it. It doesn't feel like the long-term solution, does it? Feels like a temporary fix.

“In this gentrified world, people are thinking about how space can be used differently.”

So how is club culture adapting to address these competing forces, especially that brand of it that feels a little more organic and a little more of the Wednesday night, small basement kind of club?

It's struggling to find its place. It does feel divided in terms of culture at the moment. You have the really big corporate-type events with venture capital money behind them and big ticketing agencies, or it's super niche — the stuff that isn't getting written about. There's very little in the middle. Maybe these days, the middle space has been hollowed out.

What it means to be part of club culture is changing as well. Back in the day, being part of club culture literally meant running club nights. That was the heart and soul of it. When you think of club collectives these days, they're as likely to be run as some sort of online platform or online radio station. Maybe the nights they do are much more occasional — not every Wednesday in a basement but something they do once a quarter.

On the more positive side, there are a lot of people who really care and are looking for solutions. In this gentrified world, people are thinking about how space can be used differently. Now you're getting venues that are a club at night, and maybe an education space in the daytime or a gallery, maybe some kind of co-working environment. The mixed use of space is quite interesting as a way to compete.

People are getting armed with information. So many people I spoke to for the book were really aware of how to get funding or who to go to for advice, or databases that gave you access to Black and underrepresented artists. There are tools and resources that certainly didn't exist back in the day. It feels like people are readying for the fight. But yeah, there's a lot to fight against.

At the same time, is there some risk of what you address in the book as the intellectualization of dance music? I enjoyed it in the prologue where you acknowledged that there are now even book clubs focused on raving, and you begin by acknowledging the irony that you are here writing a book on the topic.

Yeah, am I part of the problem or the solution here?

“There's the festival-ization, the museum-ificiation, the intellectualization of dance music. But what about the actual dancing?”

I don't know. I mean, I’m writing a long-form article about it. [laughs] What does that tell us?

Dance music is a hot topic. There's the festival-ization of dance music. The gentrification of dance music. The museumification of it. The academification and intellectualization of it. It can feel like people are more interested in dance music in every way other than actually dancing in clubs anymore. A lot of people love the energy it creates, but they don't necessarily want to go out there and contribute to that energy themselves.

One thing you cover quite a bit in the book is gentrification. There's a paradox where we see clubs transform neighborhoods into cultural hotspots, which then inevitably prices out those same clubs and the ravers who build community in those venues. Are there any cities that have successfully broken this cycle?

It is an inevitable feature of urban development. We've seen it time and time again, whether it's Berlin, Williamsburg, or Shoreditch. You can repeat that formula across the world, certainly across the Western world.

Many of the people I spoke to who work in club culture were cognizant of feeling that they were both one driver of gentrification, but then also victims of it. Clubs are part of that early phase of gentrification. Yeah, they're part of the problem as well.

I don't think any cities have really got a handle on it, but I did speak to lots of people who have strong tactics in mind. Probably unsurprisingly, cities like Berlin and Amsterdam seem good at it. Sydney is interesting because it went so much in the wrong direction but is pushing back now and reestablishing nightlife. London and New York seem predictably slow. New York has birthed so much night culture — it is the home of disco — but you couldn't give any credit to the authorities for the role they played. Everything was in spite of what New York was doing for its nightlife.

What I did see was loads of people exploring ideas. A lot of it focuses on urban planning and how cities after dark should be considered better than an afterthought. When you think about how you design a city, most urban planners are thinking about the daylight hours. But half of the city's lives are spent at night. So there’s more focus on how to make the night work for all people — including residents trying to get some sleep alongside people who want to be entertained.

Maybe the days of the dedicated discotheque are over, but can we create community-oriented spaces that feature DJs at night but become hubs for learning and creativity during the daytime? Places like Public Records in Brooklyn are really interesting. If governments don't want the center of their cities to be hollowed out, they might be trying to reinstall nightlife into those spaces as a positive next step.

“If governments don't want the center of their cities to be hollowed out, how about reinstall nightlife?”

The title of your book, “Selling the Night,” signals the tension at the heart of dance music — a tension between counterculture creativity and commercialization and commodification. What does that tension look like right now in 2025?

It's probably more intense than ever. We've got to this stage, reflective of a lot of society, with quite a polarized world within club culture between the haves and have-nots.

You've got the mainstream end of club culture, which looks a bit like festival culture or big venues like Drumsheds. There's lots of money there, and brands can position themselves in that world quite comfortably. Then you have the other world — the have-nots — which are free parties, unlicensed events, parties run by marginalized communities. They're not getting the same level of brand support.

Then you open up a couple of questions. Some may not actually want that support — it may be the very last thing they want — but others probably would welcome some help.

The challenge is that brand people I spoke to, who seemed well-intentioned about providing resources to these more marginalized areas in culture, need to justify it to the people upstairs. Maybe you're not reaching the numbers you would through sponsoring festivals. Maybe the KPIs are hard to prove, the metrics, all of that side of it. Brands can feel like they’re one step away from a backlash. It can go wrong much quicker, and they can get called out more readily.

The stakes feel quite high on all sides.

“I wouldn’t bet against the appeal of people getting together in a space to dance to some loud music.”

You have Jägermeister’s Save the Night fund and other examples in the book where brands have shifted from sponsorships to funds supporting nightlife. Does that represent a meaningful change in the power dynamic or simply more sophisticated branding of the same things?

It’s interesting to put it in the context of the longer journey. If we go way back, all brands did was literally turn out with posters and banners — they didn’t make any effort to contribute anything more than just slapping up the banner.

Then there was an acknowledgment that this was not authentic, so the quest for authenticity began. Some milestones along the way are brands providing documentation, creating content around things. Red Bull Music Academy was good at that — it wanted to try and tell the stories that were often untold or the lost stories of pioneers.

Then you have brands trying to enhance the experience — not only product placement but bringing something extra that the party couldn’t afford to do itself.

That has got us now to funds and grants and trusts. It seems to be the current language. To your point, it is still brands being brands. This may simply be a new wrapper for brand marketing. Brands are ultimately there to make money for shareholders. But when I spoke to people at the operating level within brands, many were really passionate with strong, good intentions about how they could make sure their brands were doing the right thing.

It’s an acknowledgment of how short-termism has affected so much. Brands will come in, sponsor clubs for a year, and then that Chief Marketing Officer will leave (they’re only hanging around for 18 months on average), a new CMO comes in, and they do something completely different. Nothing provides consistency.

If you’re a brand that has spent a long time in dance music and leveraged the creativity of Black people, people of color, queer communities, and other marginalized people, you probably have a responsibility to bring something back that isn’t just about short-term hits.

Is it really a fund? It only becomes a fund if you can take it out of the marketing department and position it somewhere else in the business, with accountability that this is something you’re doing for 25 years — not “we’re going to do it for now and see where we go.” You need to create a trust or nonprofit alongside the main corporate business, with locked-in governance and a legal structure that means the fund can’t be dissolved because of a change in marketing strategy.

The other challenge for brands is what kind of marketing to do around it. A really brave, confident brand wouldn’t market it at all. It would simply set up a fund, decide which area of dance music and club culture it felt a responsibility for and invest in it — letting those stories permeate across the subculture over time. But it’s hard for brands to hold their nerve and actually do that.

After writing this book, conducting this research, and tracking decades of cycles in club culture, do you find yourself more optimistic or pessimistic about its future?

Maybe this is a bit misguided, but I remain optimistic that it will find a way. This starts to sound a bit like some corny lyrics. [Laughs] [Links added by the editor.]

But club culture has fought so many threats, whether from government, media, bigotry, local authorities — all of these threats going back 50-plus years to disco culture and so forth.

As much as times are super tough at the moment, and things are changing quickly, it will find a way to reposition itself in our new world.

I wouldn’t bet against the appeal of people getting together in a space to dance to some loud music.

I've edited and condensed my conversation with Crysell for clarity.

“Selling the Night” is available now via Velocity Press.