Sustainable fashion’s “AI” blindspots: Why the same scrutiny isn’t applied to tech hype

Your TL;DR Briefing on things worth tracking — and talking about over your next power lunch. *Wink.* This time the thing is the cognitive dissonance in fashion around “AI.” It won’t stop the climate crisis but it might take your photographer pal's next gig.

The thing is:

For decades, an interdisciplinary movement of environmentalists, activists, scientists, journalists, designers, labor organizers and many others have vocally called for brands to address the negative impacts their businesses have throughout the supply chain. (Full disclosure: I’ve been in the fray. For instance, I conceived of and edit this annual COP report on fashion’s climate inaction. I worked on the copy for an Instagram carousel for Emma Watson’s social team about it way back in COP26 days, laughs out loud. I could go on.)

That movement picked up pace in the 2010s as fast fashion sped up. It urgently called for the industry to reduce its runaway carbon emissions. Pay garment workers living wages. End fast fashion’s linear take-make-waste business model, which sends millions of fossil fuel-derived materials to landfills where they’ll take up to centuries to decompose.

But, of course, when you look into the data on almost any consequential issue, the trend has been in the wrong direction. Why? Fast fashion. Surely, one could never honestly apply the term “sustainable” to any element of the fast fashion business model, the driver of much of the industry’s worsening impacts. It’s not a model confined to fast fashion anymore, either — it’s a way of doing business that’s also trickled over into some brands in the luxury, sportswear and other segments of the industry, where many consumers observe stuff also feels a bit trashier.

For years, this didn’t stop many of the biggest and fastest brands from appropriating sustainability messaging when it was profitable for them to do so, a topic I spoke on this week at a panel hosted by the British Fashion Council. Fast fashion brands co-opted it and greenwashed it while never really intending to implement any of what it actually could mean to become a more sustainable brand.

Certainly, fast fashion and sustainable are equally vague terms, though we can take them at face value for this briefing as volume-based business models focused on selling more clothes than the planet needs. Sustainability is, in essence, the inverse of that. A sustainable fashion industry would be one operating within planetary boundaries, respecting Indigenous knowledge and craft, and reframing our perspective on what something costs beyond the sticker price.

Sustainable fashion activists and journalists alike know this. It’s why advocacy organizations have rigorously critiqued brands’ sustainability claims through years of often fierce campaigning. And it’s why accountability journalists have vigorously reported on the disconnect between what brands say and what’s happening in their supply chains. And yet, the floor from fast fashion has lowered to ultra fast fashion. The failure isn’t on the part of the movement calling for brands to do the right thing. It’s the incentives in our current fashion system working as one could expect they would.

But that’s why it’s so ironic to observe some in the sustainable fashion space not applying the same critical lens to the environmental and human rights concerns to another industry’s complex and opaque supply chain: “AI.” Worse, some in the sustainable fashion space have become deluded with the grandiose claims spun by Big Tech; they’ve fallen prey to techno-solutionism. And that might prove to be a distraction from implementing actual solutions.

All the while, the more harmful effects of the tech hype are already visible. Synthetically generated designs are becoming synthetic garments, speeding up all elements of the fast fashion (dis)value chain from design theft through to the promotional slop. In doing so, experts warn that using “AI” to speed up this production could further “fuel overconsumption,” lead to brands “breaching copyrights” and maybe resulting in an “algorithmic monoculture,” as Time reported last year.

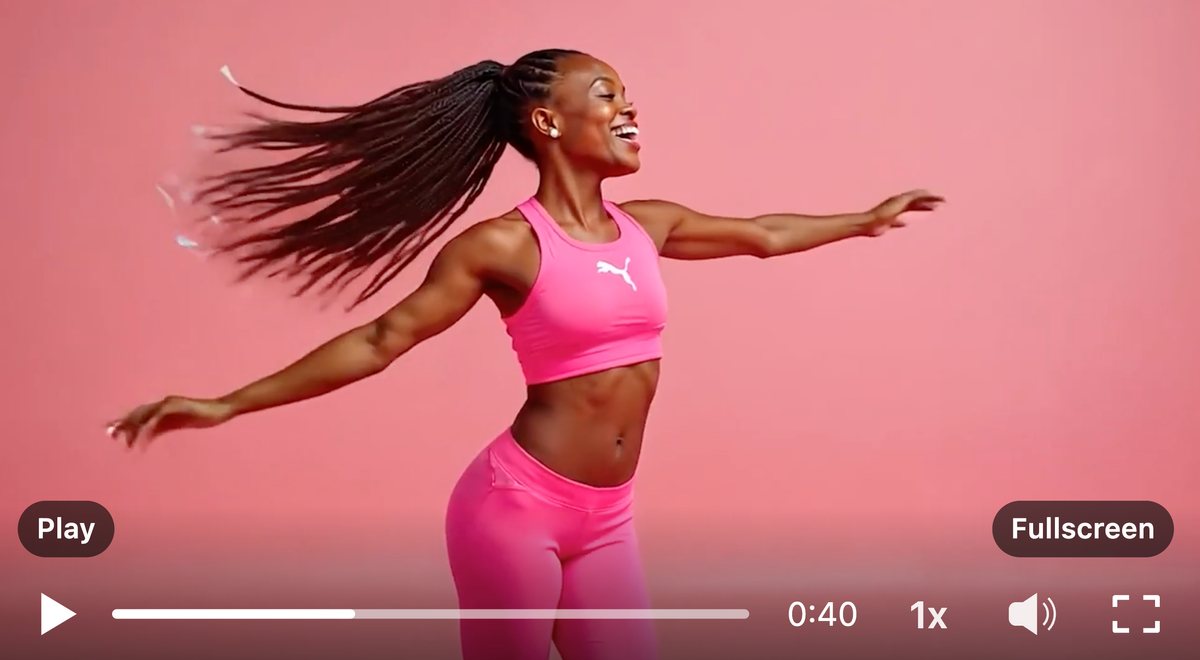

To that end, one artist filed a lawsuit against ultra-fast fashion giant SHEIN last April for using generative “AI” to allegedly copy their work. Fast fashion brand Mango even replaced human models with “AI models” in a recent campaign. Meanwhile, synthetic articles generated by “AI” appear designed to greenwash the search engine result pages when someone googled Temu, Ethical Consumer wrote last year. And most absurdly, Puma released an experimental campaign where they bypassed human creative teams altogether and used so-called “AI agents to create an ad from scratch,” as Ad Age reported last week. Joining up these dots reveals how unquestioned tech hype is often little more than a red herring, and we’re all paying for it.

The thing about that is:

This week, a gathering of the fashion industry in London connected a few disparate threads in my mind about the failure of what some refer to as “techno-solutionism,” the idea that every problem is a problem to be solved through technology. (It is not.)

“We already have the solutions” — that was a sentiment I heard repeated several times on Thursday at the fifth-annual Institute of Positive Fashion (IPF) Forum. Fashion is, in many ways, a low-tech industry — decarbonizing factories, for instance, doesn’t really require new technology. It requires brands helping their suppliers upgrade to renewable forms of energy, among other interventions. It’s not hard to imagine the solutions. It’s much harder to imagine modern day brands, who maximize profits for shareholders, paying the bill. The implication is that issues such as decarbonizing fashion’s supply chain can be done. It is not easy. But what’s missing is, of course, action and investment to make progress.

Those are the kinds of conversations you get into at the IPF Forum, an always motivational day of sessions hosted by the British Fashion Council at 180 Studios. The event brings together a diverse crowd: brands, journalists, student designers, NGOs, activists, policy wonks and even a few elected officials.

I was there speaking about my editorial work in the fashion sector — on a panel about communications strategy, moderated by Kati Chitrakorn, editor for CNN Style, and joined by several compelling speakers from small and large brands (upcycling innovators ELV Denim, top-rated B Corp DEPLOY and British heritage brand Mulberry).

The key takeaway from my panel was, yes, there are many creative opportunities to engage culture and to galvanize citizens to act. But ultimately sustainable business practices and supply chain transparency need to happen before a brand attempts a feel-good campaign. As much as we expect consumers to “vote with their wallets,” as the line often goes, we should be expecting brands to do so even more. And I sensed a level of frustration from some in the room that we’ve been talking about many of the same things for more than a decade.

This era defined by way too much cheap trash is, after all, not the only model that exists — in fact, some readers will remember a fashion system before fast fashion. In many parts of the world, more sustainable models exist in practice, on a small and localized scale. In that view, the solution might look like less tech rather than more — slowing down rather than speeding up.

“We have a long recovery ahead of us and I believe that if those of us who work in fashion cannot be honest about something as simple as production volumes, then we are not ready for the colossal task of transitioning our industry from disposable to circular,” Liz Ricketts, founder and executive director of the Or Foundation, wrote in September in Teen Vogue. “Being honest about overproduction will not end fashion; it will save it.” That was the sentiment I took away from the event, too.

Certainly, there is a case for investing in truly innovative technologies such as textile-to-textile recycling — especially given how many synthetic blended fibers end up wasted, mounding up in piles you can literally see from space. But even here, isn’t the more urgent problem addressing the root cause of all this waste, the overproduction of that many clothes in the first place?

Where things get interesting:

Karen Hao, award-winning investigative reporter and co-creator of the Pulitzer Center’s AI Spotlight Series, recently spoke to ESC KEY .CO, in which she told me that well-meaning journalists themselves have got caught up in the hype, too. The training program she leads at the Pulitzer Center helps arm journalists with the skills to deliver the accountability journalism for “AI” that the public needs.

My ears perked when Hao drew a line to another industry where accountability journalism is key to informing consumers: “I sort of analogize it a little bit to fair trade and the fashion supply chain. There was such great reporting at the time on the fashion industry and how we do not actually need clothes that lead to human rights abuses.”

It felt a bit, well, circular that accountability journalism in fashion was informing accountability journalists in tech to scrutinize the supply chain for generative “AI” systems like large language models — a connection, I told Hao during our interview, that many in sustainable fashion don’t seem to be making themselves. She says the press has a role to play in helping the public see that “AI doesn't just arrive fully formed.” “There are real economies of scale, economies of extraction, labor exploitation and data exploitation that are churning beneath the surface to produce this technology in the first place,” Hao explains in this curious reader’s guide to hype-busting “AI.”

The point is not to imply the supply chains are the same; they are not. It's to implore us to expand our critical imagination.

Perhaps the most common mistake fashion professionals make is one journalists often make, too: using “AI” as a catch-all term. “There are many different types of AI technologies, and it’s really hard to understand which technology you’re talking about when you just use the term AI,” Hao points out. This blanket terminology obscures critical distinctions between vastly different systems with dramatically different impacts.

Take environmental effects. Some outlets publish stories claiming both “AI could be really bad for the environment, but it could also somehow help tackle climate change,” she’s noticed. And she’s dug into this in her own reporting — often claims from tech companies about some “future technology” might address some environmental issue. Not only is this vaporware. It often amounts to greenwashing. The reality is more nuanced. Generative “AI” models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 require massive data centers, consuming extraordinary amounts of energy and water. The supply chain of human laborers from miners (and everything else entailed in creating the infrastructure needed for all those chips and data centers) through to data labelers (the people who tag all the data to train models) and beyond is rife with exploitative practices.

Conversely, some technology advertised as “AI” isn’t a part of that particular supply chain — but the companies promoting the tech are just bandwagoning on the hype.

Essentially, saying “AI” is as about as specific and clear as saying you’re a “conscious” brand.

Sustainable fashion pros would not accept unverified claims about, say, a novel fiber being lower impact without first expecting thorough life-cycle assessments. And yet the lack of critical consideration for “AI” systems have some buying into hype that’s ultimately a distraction from the real problems.

The thing to talk about over your next power lunch:

What happens when brands buy into the “AI” hype — and who gets harmed?

Recently, I was chatting with a photographer, who has several fashion brands as clients. One of those clients had sent them a link to a blog post from commerce startup Photoroom, which claimed “AI” image generators could “cut your carbon footprint.” How would it cut a brand’s carbon footprint? By cutting the creative team, which is clearly where brands should be looking to cut their emissions first — not, I don’t know, in the actual supply chain.

“A recent study reveals that the carbon dioxide equivalent emitted from creating an image with AI is significantly lower, ranging from 310 to 2900 times less, than the emissions associated with human-led photo production,” reads the Photoroom blog, which cites a surreal 2023 study that was subsequently skewered on an episode of the podcast Mystery AI Hype Theater 3000.

Needless to say that the framing of that study sounds like it’s suggesting murdering photographers, illustrators, writers and designers to reduce the “carbon footprint” of the creative industries. (Need we remind you that “carbon footprint” was itself a PR distraction created by fossil fuel company BP with its advertising agency.) But, dear reader, this is, in fact, the kind of conversation that professional photographers are today having with some brands, even brands that might position themselves as sustainable.

Recently, journalist Megan Doyle, in an article for Vogue Business, hit on what’s going on here — in a lot of cases, with generative “AI” in creative work, the motivator for brands is the bottom line. “The main reason brands come to us is to save on costs and time,” the founder of an “AI” agency working with fashion brands said. “To be perfectly honest, [sustainability] is not something that is being talked about.”

It’s tempting to chalk this up to fashion’s obsession with trends, which has only worsened as fashion has become its own kind of entertainment category. There’s an argument one could make that the current state of experimental “AI” ads like Puma’s, “AI” fashion weeks and so forth is simply another gimmick in the vein of NFTs and the “metaverse,” whatever you think that is.

But it hits different when you have friends in this industry who are worried about losing work to cost-cutting clients who’d like to position their synthetic campaign as “sustainable.”

It’s Orwellian in many ways. It may negatively affect the demand for freelance photography work. And where it’s not keeping photographers from a gig, the many concerned creative professionals will see this as contributing to the growth of synthetic spam content on the internet. Engagement on certain social media platforms may spike in the short term. But at what cost? In the long term, it’s hard to see where this is anything but another case study in “AI-sterity — that’s austerity, but now with ‘AI!’”

Do we even need to conclude by saying that synthetic image generators are not going to move the needle on a brand’s carbon footprint? Do we need to repeat the fact that many, though not all, generative “AI” text-to-image models were trained on stolen data? As for really addressing fashion’s impacts? We already have solutions. Let’s refocus on those.

And one long thing to read:

This TL;DR Briefing features one of the three red flags revealed in this guide to hype-busting “AI” — and it gives you a simple framework for how to read the emerging tech hype: