Anti-hustle culture but can’t stop hustling? Paul Lafargue would like a word with you

Your TL;DR Briefing on things worth tracking — and talking about over your next power lunch. *Wink.* This time the thing is “The Right to Be Lazy,” a wildly timely 1883 book and the first selection for the new Public Domain Reading Club.

The thing is:

How many times have you looked at some modern problem and thought, hm, that's not exactly new though, is it? For instance, maybe you’re a freelancer who lived through the Great Recession, which makes the current age of “AI-sterity” feel a bit déjà vu — another “pivot” further devoid of humanity? We journalists would often say in the early aughts, “print dollars are digital dimes,” referring to tanking ad revenues that led to more layoffs. Maybe those digital dimes are now “AI” pennies, as bosses think they can use bullshitting chatbots to replace human writers? That is, after all, happening all around.

Our current predicaments often feel like new iterations of the same underlying dynamics, particularly when it comes to technology, work and power. That’s why I’m stoked to unveil the first selection in the new Public Domain Reading Club: Paul Lafargue’s “The Right to Be Lazy” (1883), a short book that feels shockingly relevant to our current era. The title is, yes, a little click-baity. His argument isn’t really about doing nothing with our lives, but rather about who benefits from all this overwork and how we might change that.

Today, we’ve published the full pamphlet in its original translation directly on ESC KEY .CO. This briefing touches on the key ideas you need to know even if you don’t want to read the whole thing (but c’mon, pal — it won’t be a reading club without thee!).

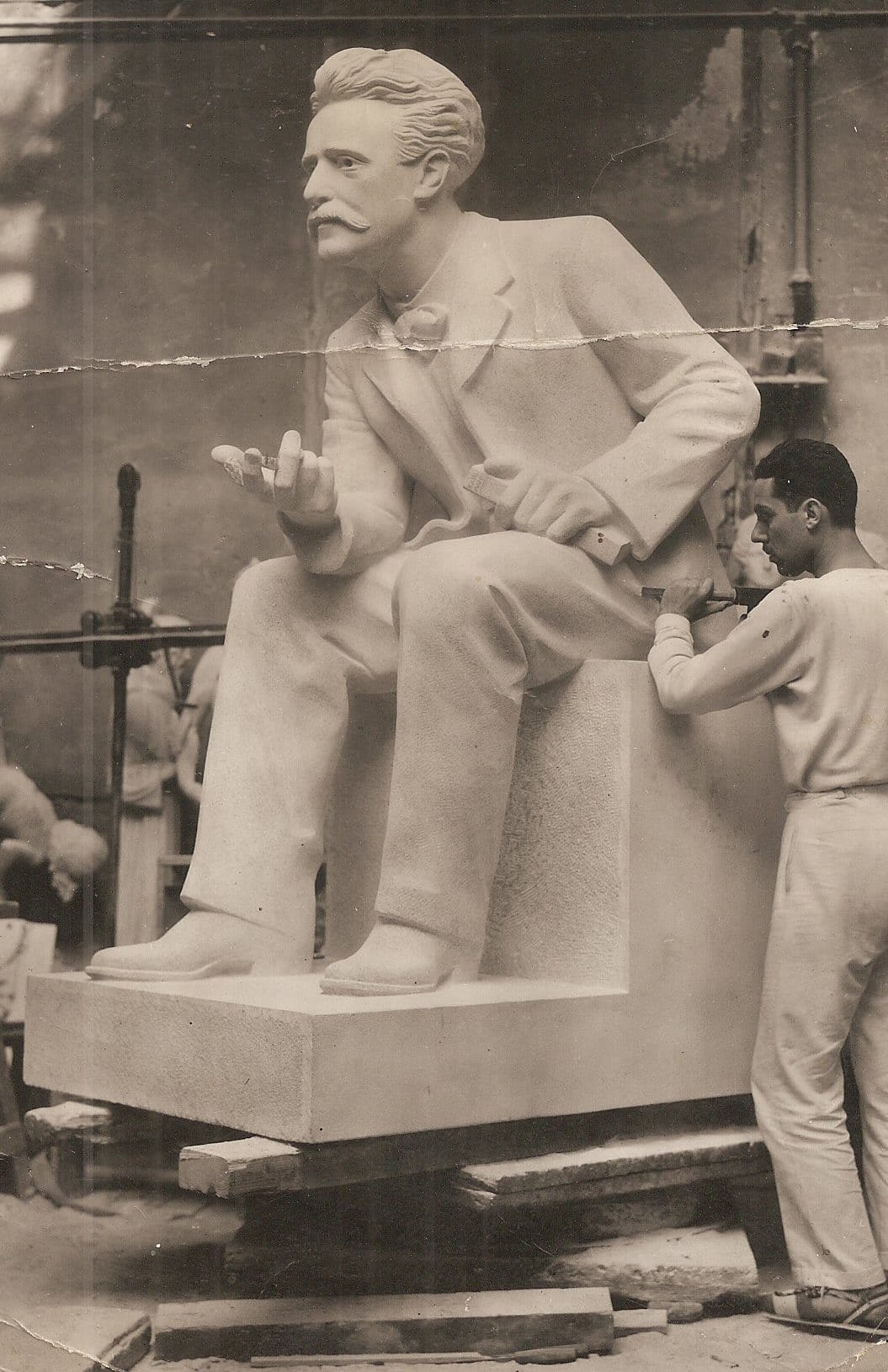

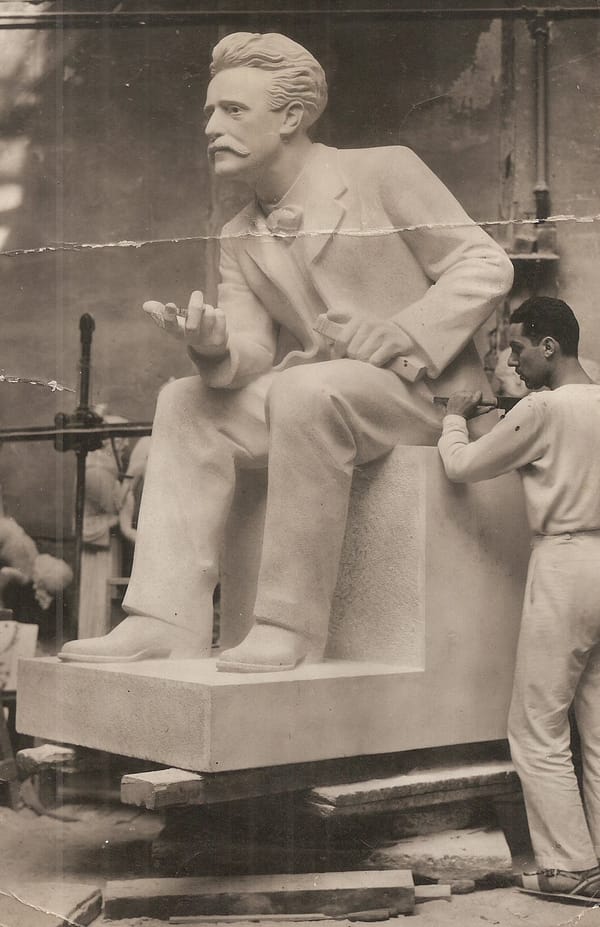

Written from the notorious Saint-Pélagie Prison in Paris by Karl Marx’s son-in-law, this witty polemic begins with a paradox: workers have been conditioned to maintain their own exploitation. While machines should in theory make labor easier, Lafargue argues that in practice they're ultimately transformed into tools that intensify human toil (i.e., the productivity gains don't give you more time off; they increase profitability). The working classes, he writes, have been deluded into serving a system that treats them as disposable.

Arguably, any creative and knowledge worker today probably relates to some of that. You don’t need to self-identify as a Marxist, or ever have read anything by Lafargue’s father-in-law, to see how that analysis maps to much of what's wrong with work today.

In short, his argument goes that machines are only our saviors if the time they save us goes toward giving us more time to live.

The first couple of chapters drag a bit. But the most striking passages come in chapter three, where Lafargue gets into the automation paradox:

“The blind, perverse and murderous passion for work transforms the liberating machine into an instrument for the enslavement of free men” (and, like, everyone regardless of gender).

He hits hard. He notes that while a knitting machine produces “30,000 [meshes] in the same time” as a worker’s five, giving workers “ten days of rest” for every minute of machine labor, the opposite occurs in practice:

“In proportion as the machine is improved and performs man’s work with an ever increasing rapidity and exactness, the laborer, instead of prolonging his former rest times, redoubles his ardor, as if he wished to rival the machine. O, absurd and murderous competition!”

The thing about that is:

Lafargue was born in Cuba to a family with Jamaican, Haitian, French and Jewish heritage. After moving to France and later London, he met and married Karl Marx’s daughter, Laura. Yet Lafargue faced racism within leftist circles. As Nicholas Burman wrote in Tribune magazine in a 2022 retrospective, “both [Friedrich] Engels and Marx supported Lafargue, and Lafargue played an indispensable role in popularizing Marxism in France,” and yet “the two would dehumanize Lafargue by using ethnic slurs when referring to him. Lafargue’s mixed-race status appears to have been used against him to delegitimize his role in the development of the left.”

This historical sidelining partly explains why “The Right to Be Lazy” isn’t as canonical as it might’ve otherwise been. Lafargue was writing during the Second Industrial Revolution, when mechanization was transforming European economies and concentrating wealth in unprecedented ways. Factories were implementing new systems that could produce goods at staggering rates, yet workers found themselves laboring longer hours rather than enjoying the fruits of this productivity.

The paradox Lafargue identified remains with us today, even as labor movements have achieved much: technological advancement fails to deliver on the repeated promises of reducing human toil. As Idler magazine editor Tom Hodgkinson (aka “the hardest working man in slow business”) observed in a 2023 interview about Lafargue’s work:

“Technology always announces itself as, you know, we’re going to free you from toils so you have more time to do the things that you love. And then, in fact, the opposite happens and people end up working longer and longer hours and being more and more tired.”

This pattern repeats with remarkable consistency. The economic gains from improved productivity rarely trickle down to workers in the form of shorter hours or better conditions (that is, not without considerable labor organizing for, say, five-day workweeks and eight-hour workdays). Instead, we get mass layoffs, more lavish sacrifices to the god of “optimization” and our surveillants’ expectation that we should always be available. Earlier this month, CEO Tobias Lütke said Shopify won’t hire anyone unless a manager can prove that “AI” can’t do the job (well, *shrug,* we shall see how well that goes).

What’s even more striking is how thoroughly this system has trained us to embrace our own exhaustion as virtue — the delusion Lafargue called “the furious passion for work.”

Where things get interesting:

We’re living through what the World Economic Forum’s Klaus Schwab has dubbed the “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” characterized by “AI,” automation and digital platforms. Yet the patterns Lafargue identified remain remarkably consistent even in this latest season. The automation paradox has simply found new expressions in our terminally online era.

We’re in a surreal moment where broligarchs like Elon Musk say things like “AI” represents “the most disruptive force in history” that might lead to a “point where no job is needed,” as Musk told British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in 2023. Yet these rosy pronouncements stand in stark contrast to Musk’s policies. In leading the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), he’s implementing “AI-sterity” and mass layoffs throughout the federal government. As Charlie Warzel noted in The Atlantic, this amounts to a “bureaucratic coup” led by an unelected billionaire. It’s also a stark contrast to what Musk tweeted on X recently: “We need to shift people from low to negative productivity jobs in government to high productivity jobs in manufacturing.” Hm.

Far from creating a workless utopia, our current technological revolution has created new forms of human exploitation. Data workers and content moderators — often located in the so-called Global South — provide the hidden human labor that makes “AI” systems function. These workers review disturbing content, label training data and perform the repetitive digital piecework that undergirds our supposedly automated systems. As Karen Hao, author of “Empire of AI,” recently told ESC KEY .CO, we need to resist viewing technologies such as large language models as some disembodied intelligence in a formless “cloud.” Instead, recognize it as a product with human rights and environmental issues throughout the supply chain. It’s much the same playbook that Lafargue described in 1883.

You might ask, “But what about [...]?!” (Ugh, hello, Steven Pinker.) In as much as, say, post-war economies in the United States and Europe helped lift many out of poverty and improved life spans, much of that was ultimately attained through socialist-lite policies such as the GI Bill. The GI Bill provided universal college education to white U.S. veterans. More so, it was achieved through relentless labor organizing such as the mid-20th century union efforts that led to improved work conditions for, as Bernie Sanders reminded us in the 2016 election, Denmark (true for worker-led movements around the world, too). The protections we enjoy today came through long-term movements, solidarity and collective action.

Technology does not achieve progress for workers. Workers achieve progress for themselves.

Even so, the worst of industrialized exploitation was mostly outsourced and offshored — repeating patterns of colonialism that continue in today’s tech supply chains for everything from cell phones to chatbots.

In the context of Big Tech's “AI” hype, the Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR) has recognized this reality in 2024 when they unveiled the Data Workers’ Inquiry project, which adapts Marx’s 1880 Workers’ Inquiry methodology to understand the experiences of “data workers who are both essential for contemporary AI applications yet precariously employed — if at all — and politically dispersed.” As Fasica Berhane Gebrekidan wrote about the experiences working as a data worker in Nairobi:

“Content moderators risk their lives to train AI machines and algorithms, yet are only compensated with low pay and poor working conditions and are left with mental health issues and addiction problems. [...] These jobs destroy many young lives.”

The thing to talk about over your next power lunch:

Ultimately, what makes “The Right to Be Lazy” particularly engaging is its biting wit. As Alex Andriesse, associate editor at the New York Review Books, said in a 2023 interview about his new translation:

“To me part of the interest of it is that he sounds like he’s constantly joking or being hyperbolic but he’s really barely joking and barely being hyperbolic as he talks about how the capitalists, the owners, the proprietors have sort of taken advantage of this just to line their own pockets without any concern for the people whose lives are being eaten up by these machines.”

It explains why the pamphlet has remained a cult classic among critics for generations.

Equally, though, it’s easy to poke holes in some of Lafargue’s more utopian impulses. Perhaps due to what Mark Fisher termed capitalist realism, it can read like it’s entirely detached from working class reality.

It’s also important to acknowledge where Lafargue’s text shows its age. His racist romanticization of so-called “primitive” societies and some other misguided references reflect colonial, European-centric perspectives that we’re still grappling with today. His focus on industrial labor, as well, overlooks domestic work and caring for a family.

Reading historical texts requires this context: we can learn from the enduring ideas while drawing a line around the limitations. What happens when we read the text not to “agree” with it but to challenge our own assumptions and expand our own sense of what might be possible?

In that way, it’s not hard to see his writing as a footnote to so much current writing about burnout, overwork, productivity porn, quiet quitting, the pandemic-era Great Resignation, our current recession fears, you name it. From David Graeber’s “Bullshit Jobs: A Theory” to Jenny Odell’s “How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy,” today’s critics are updating elements of Lafargue’s central thesis. The four-day workweek trials across the UK and elsewhere, showing maintained or increased productivity with reduced hours, seem to flow from these century-old arguments even if uncredited.

Why haven’t we claimed this “right to be lazy” yet? To the contrary, many of us have accepted “AI-sterity” as inevitable rather than a choice. (That may be because, as with the case of Shopify workers who are now obliged to use “AI,” it isn’t a choice.) Too many of us, like the proletariat in Lafargue’s age, have strapped our critical imaginations to these new industrial machines.

What I find so fascinating in rereading “The Right to Be Lazy” isn’t so much the early Marxist theory or the analysis of 19th century labor. Rather, it’s the provocative prompt for us to ask, what would truly democratizing technology look like in the benefit of society, not shareholders? Perhaps most crucially, what would happen if we, collectively, started treating time offline not as an indulgence but as central to, you know, being human? Maybe a less click-bait-y title could be “The Right to Live a Chill Life and Hang Out With Family and Friends”?!

And yet, how difficult is it to even imagine such a world? Our culture has so thoroughly internalized “work as virtue” that questioning it feels almost blasphemous.

The words “lazy” and “idle” are still powerful slurs. If you’re wondering, wow, this all sounds great, but how do you do it, JD?! I'll confess that while writing this briefing on a public holiday, I checked my time-tracking app and found I’ve averaged 60 or so hours of work weekly over the past year. In other words, intellectually “anti-hustle culture” while practically keeping myself in servitude to the boss girl hustle.

As Lafargue puts it, with his characteristic wit:

“O Laziness, have pity on our long misery! O Laziness, mother of the arts and noble virtues, be thou the balm of human anguish!”

And one long thing to read:

To make it easy to read, reference and share, we’re republishing the original 1883 translation by Charles Kerr, the pioneering Chicago, Illinois-based publisher who the United States government denied mailing privileges to. The government then alleged books like this one to be seditious violations of the Espionage Act of 1917. Read “The Right to Be Lazy” in full: