How to hype-bust “AI” bullshit: A curious reader’s guide with the Pulitzer Center’s Karen Hao

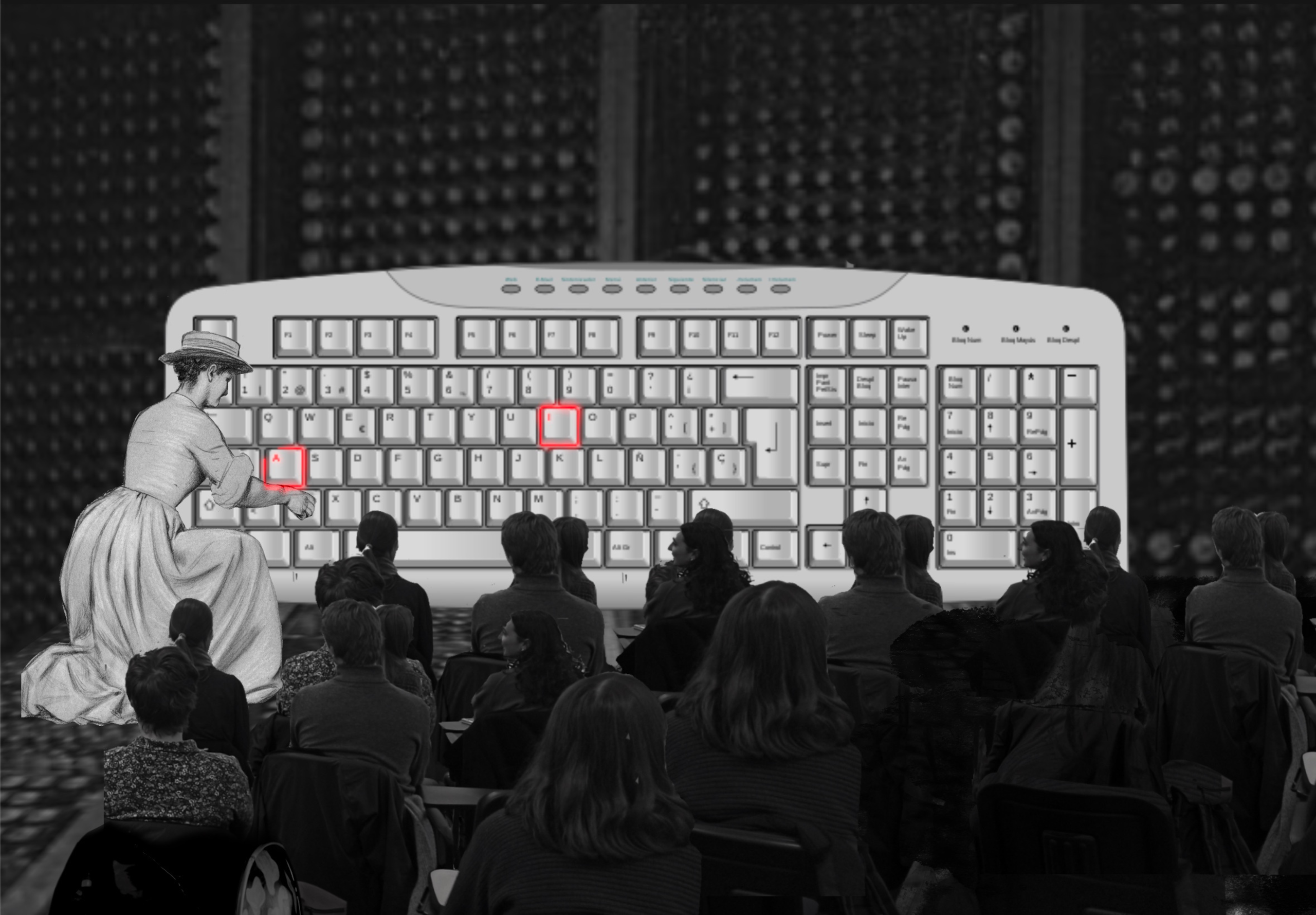

What are red flags for spotting the spin? Award-winning investigative reporter and co-creator of the Pulitzer Center’s AI Spotlight Series, Karen Hao reveals a simple framework for readers who want to embrace skeptical curiosity and hit, well, the ESC key on the hype.

Maybe you’ve heard this one before: so-called “AI scientists” are allegedly entering science. Or how about this one: “Virtual employees” will soon be your colleagues, maybe even replacing your “CFO” who will “determine who gets laid off.” And this one, too: “AI” will be a “help rather than hindrance in hitting climate targets.” (That’s, of course, the punchline.)

These are only a few of the absurd examples of “AI” hype narratives created by those who stand to profit from its development, then repeated time and again as if they were facts.

These are not, however, examples only repeated by the cringe LinkedInfluencers, who one might expect to squawk about the latest press releases because of their grift. These are, in fact, a few of many examples parroted by reputable publications. Today, tech and media literacy are becoming important bulwarks in this twisted information ecosystem.

Imagine unshaven Rip Van Winkle waking up to this hype cycle

Yes, unless you are literally Rip Van Fucking Winkle, you know the essential context. Since OpenAI’s ChatGPT public launch became a viral phenomenon in November 2022 and the subsequent Big Tech race to build as many data centers as possible, the reality-distorting claims about what the tech might one day be able to do continue to confuse people about what “AI” actually is doing right now.

The distractions are aplenty. Is it a danger to humanity? Are we in for an inevitable “paper clip” apocalypse caused by some “paperclip-making AI,” as one eugenicist philosopher speculated in a thought experiment?! Or are we witnessing the dawn of some life-saving, productivity-boosting era, even some kind of utopia where, as Elon Musk has suggested, nobody will need to work?! The spectrum of competing ideologies are so detached from present reality and from present harms, that you might want to tune it all out.

It’s exhausting. But as the hype wheel has picked up speed, the discourse in creative industries and knowledge work gets whipped up into frothy FOMO — fear of missing out on powerful technology, of seeming like you’re anti-progress, of being left behind or risking your career in the process. That FOMO partly explains the prevalence of synthetic slop content that has made my LinkedIn feed even more cringe than it already was, if that’s possible. Seemingly everyone is an “AI expert” now. Seemingly everyone wants you to sign up to their “AI” newsletter (“follow me to learn how you can leverage AI to 10x your productivity and accelerate your career,” one popular “AI LinkedInfluencer” writes on their profile). Seemingly every agency that was on about NFTs before are now on about “AI” “democratizing creativity” and related bullshit. Seemingly everything is now an “AI agent.” Startups, especially those that five years ago would’ve branded themselves as “no code,” have rushed to add “AI” and “agent” to seemingly every pitch deck and product feature description. And good luck buying a dot-ai web domain — the surging demand for Anguilla's country-code domain has generated millions in revenue for the Caribbean island in the past couple years.

The isn’t only about the trendy popularity of chatbots powered by LLMs, which can seem to users like confident authorities based on the content they generate (even when spewing synthetic nonsense).

The conflicting narratives we encounter are also about a whole lot of cash. Historic levels of venture capital investment fuel hype in a sector dominated by a few competing corporations and billionaires. (“The same people cycle between selling AGI utopia and doom,” computer scientist Timnit Gebru, founder of the Distributed AI Research Institute, told the New Yorker last March. “They are all endowed and funded by the tech billionaires who build all the systems we’re supposed to be worried about making us extinct.”)

“It’s hard to expect the public to have AI literacy when many journalists aren’t demonstrating it.”

Whether by intention or not, the press becomes part of the lifecycle of that hype — in the most egregious examples, journalists essentially repackage a press release’s talking points. That’s not new. That’s especially common in lifestyle media, which tends to do the same with any sufficiently promoted thing. It’s less a conspiracy but a known driver of the business model for the glossies throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, who sell ads adjacent to the trend du jour.

In our present context, there are several notable exceptions. There are many talented tech reporters, independent newsletter writers, podcasters, a few academics with an active public profile and a handful of tech publications worth their salt.

But even the most seemingly scrupulous news outlets have, at times, gotten swept up in the vortex. It has only served to confuse the public at a moment when critical and ethical tech literacy is becoming a vital — and still rare — skill.

The Pulitzer Center’s mission to train journalists — and what readers need to know

It’s hard to expect the public to have a level of literacy on the subject when many journalists aren’t demonstrating such literacy in their own reporting. In the traditional political conception of the role of the press in a democratic society, it is the job of the Fourth Estate to help readers see through the promotional narratives and to keep power in check. But on emerging tech throughout the past decade, especially in the case of “AI,” we too often see journalists get tangled up in the spin themselves, often dedicating precious reporting budgets to chasing some “AI” red herring or thought experiments that don’t serve anybody but the companies and governments backing the “AI” arms race.

Simply glance at the day’s news and you’re likely to see such examples of “AI” hype popping up in leading news outlets, magazines, trade publications and academic journals. While not properly contextualizing claims, a meaningful percentage of journalists also frequently quote tech executives as the experts, implying that their words are the unquestioned truth.

In the press, the confusion begins at the most basic level with the unclear terminology journalists too often repeat, particularly the use of “artificial intelligence” in the singular sense, as if it were one specific kind of technology. It’s one of several red flags investigative journalist Karen Hao identifies for readers to look out for.

You can understand then why she begins the Pulitzer Center's new training program for journalists, the AI Spotlight Series, with a definition. I joined a late January training co-hosted by non-profit fact-checking organization Africa Check and the Pulitzer Center. Hao, the series co-creator and lead designer, introduced “AI” in the plural sense as “a name for a grab bag of technologies that are supposed to mimic human capabilities.”

Few journalists have covered this fast moving story as comprehensively and rigorously as Hao, a former foreign correspondent covering China’s technology sector for the Wall Street Journal, senior editor at MIT Technology Review and contributor to The Atlantic. Since long before OpenAI was a household name, she has tracked both the technical evolution of “AI” and the narratives that shape how we understand it. (She came to journalism after first receiving her bachelor’s in mechanical engineering and minoring in energy studies at MIT.)

For her forthcoming book, “Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI,” out this May in the United States via Penguin Random House, Hao brings readers inside the company that sparked the current generative “AI” frenzy. She lays out how we’ve entered a new era of empire and traces the underreported supply chain of generative “AI” — its extractive, resource intensive development across continents. This is a story told through perspectives ranging from engineers in Silicon Valley to data laborers in Africa and water activists in South America.

“It’s a field shaped by familiar human forces: money, power and ideologies.”

Hao’s reporting on “AI” through the lens of empire supports a key point she makes early on in the AI Spotlight Series training. For the accountability journalism that the public urgently needs more of, she explains that journalists should approach “AI” not as some science fiction novelty, or a (false) binary between dystopia and utopia. Rather, it’s a field shaped by familiar human forces: money, power and ideologies, she laid out in January to a multinational audience of journalists in the one workshop I attended. That’s key to the program’s mission.

Launched in April 2024, the AI Spotlight Series began with a goal to train 1,000 journalists in its first two years on “how to report on AI as the political, economic, and social story that it is,” Hao tells ESC KEY .CO — but the demand was even greater than anticipated. They quickly blew past their two-year target before the end of year one. In fact, they’d totaled twice that number.

The goal for the program, as it enters its second year? “Reaching as many journalists globally as possible,” she tells me. “Any journalist in any context, whether they are from a country developing it or having AI exported to them, should feel ownership of covering the way that AI is impacting their communities. I mean, literally, it’s affecting every possible beat in the world. And whatever expertise you have is something that can absolutely be brought to the table for more nuanced reporting.”

But what if you’re not a journalist and you still want to know how to separate hype from meaningful reporting? I wanted to know what advice Hao might offer to curious readers who want to be similarly engaged but might not have access to the Pulitzer Center’s courses — the ones scrolling through feeds wondering if that latest “AI” headline is investor bait or a truly, well, actionable insight.

In the lead up to her book’s launch, she walked ESC KEY .CO through refreshingly straightforward answers: the same critical framework works whether you’re writing the story or reading it. The patterns that reveal when you’re being sold a narrative instead of being informed about a technology — and conversely, the signals that someone’s done genuine accountability work — create a kind of cognitive sieve for the weekly torrent of “AI” news.

It’s useful no matter your personal opinions about “AI,” generally speaking. In fact, sometimes even the most vocal “AI” critics on social media don’t always sound that much more informed about how, say, LLMs work than those implying they can “read” like a human does. It’s critical, then, for readers to see the technologies often grouped together under the umbrella “AI” more clearly: what they are, how they work and whose wallets they’re designed to fatten.

But to understand why these patterns emerge, we need to begin with where the terminology came from in the first place.

First step, start at the roots — “AI” as sci-fi quest and marketing ploy

On May 9, 1973, an audience gathered for a televised debate at the Royal Institution in London. Broadcast on the BBC’s “Controversy” series, the debate followed the publication of “Artificial Intelligence: A General Survey,” a paper authored by applied mathematician James Lighthill and commissioned by the British Science Research Council. Commonly referred to as the Lighthill report, the paper evaluated the state of research in the field of “AI,” ultimately concluding that discoveries in the field were then not delivering on the major promises. The paper heralded what some call an “AI winter,” a recession in funding and interest in the field.

The debate saw Lighthill face off against three leading “AI” researchers: Donald Michie, Richard Gregory and John McCarthy. The topic of the debate? “The general purpose robot is a mirage.”

Midway through the program, McCarthy interrupts Lighthill: “Excuse me, I invented the term artificial intelligence,” McCarthy says. “I invented it because we had to do something to get money for a summer study.” Lighthill and the audience in the Royal Institution erupt in laughter.

This is why Hao thinks curious readers should firstly know that “AI” is foremost a marketing term. “[McCarthy] just says straight out of the gate that basically, the intent of this term was that he really wanted to attract attention and attract money,” she tells me. She explains that in the 1950s, McCarthy’s colleague, Claude Shannon, was against terming the field artificial intelligence. Why? “Because he felt like it would overhype the capabilities [of the tech at the time]. He felt that it could create some misunderstandings, particularly among the lay audience. It would overpromise and so forth.”

In the AI Spotlight Series, Hao begins by retracing the origin story of the field of “AI” because that’s how she came to understand the roots of competing ideologies when she began in the field as a reporter. She has the same advice to readers who want to be more engaged with the subject, too. “When I first started covering AI, I found it really helpful to just learn about where AI came from — to start to understand why we see certain discourse around the technology today,” she explains.

Therefore, she thinks it’s also important to understand that “AI” is primarily an idea, a quest to mimic human intelligence. “Over the decades since the original idea was conceived and the term was coined in the 1950s, there’s just been many different iterations of what the technology actually looks like and how it works.”

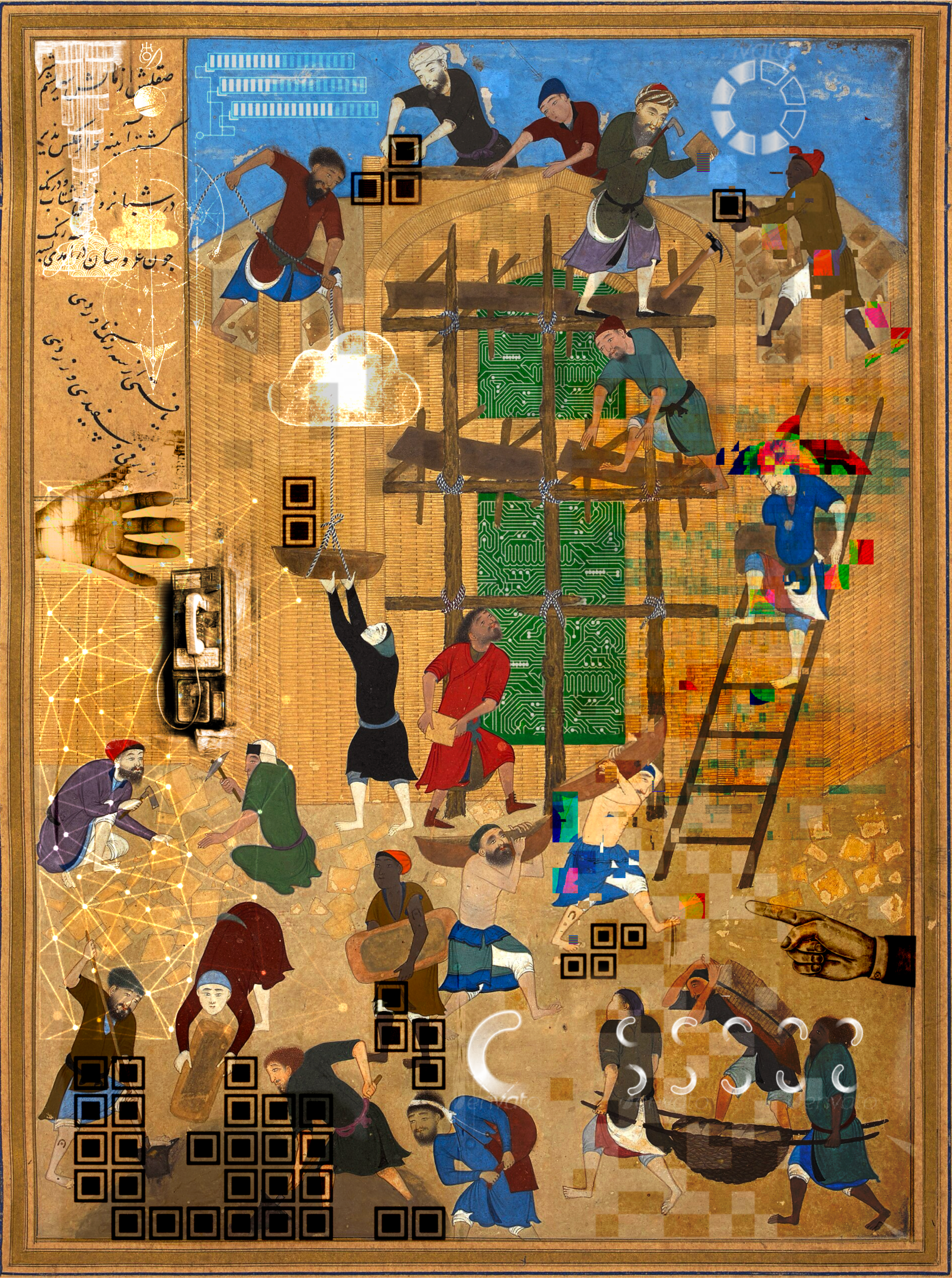

What began in the ’50s as a quest among academics to mimic human reasoning through rule-based systems has since evolved into the Big Tech race to achieve some oracle-like “artificial general intelligence.” The recent trend, especially with large language models (LLMs), is towards more and more data. That necessitates bigger and bigger compute. For instance, OpenAI’s GPT-2 (2019) had 1.5 billion parameters; GPT-4 (2023) had an estimated 1.8 trillion.

Understanding who is behind the big data, big compute vision for “AI” is key, Hao says. “There has been so much debate and disagreement for what ultimately will be required to achieve this kind of ultimate quest. And increasingly, this is not a scientific debate, but actually a business debate, a political debate, an economic debate.”

Today, the primary actors are corporations and state actors. “They have specific agendas around how the technology should be developed and what purpose it should serve. Ultimately, theirs are very self-interested agendas,” she says.

These forces shape the way the field of “AI” looks — what technologies are developed, whose interests they serve and what narratives get the most airtime. It’s why the hype has largely served to benefit the biggest U.S. tech companies of the day — and why the leaner, more cost-efficient Chinese DeepSeek startup has been described by some as the field’s “Sputnik moment.”

Understanding those two facts of the “AI” origin story — that it started as a marketing play and has become a quest shaped by the ideologies and agendas of different people and actors throughout the decades — is key. “It helps contextualize where we are today, where AI is just so overhyped and the analogies that people make between AI and human intelligence are always fraught, confusing and don’t necessarily lead to better public understanding.”

“The biggest red flag is anthropomorphizing AI.”

Three red flags suggesting you’re reading fluff that’s repeating the “AI” hype

McCarthy’s candid admission about coining “artificial intelligence” to secure funding offers a perfect lens for examining present coverage. Nearly seven decades later, the same dynamics are playing out at a vastly larger scale.

Hao identifies three red flags that signal when you’re being sold a narrative rather than informed about a technology.

🚩 Describing “AI” like it’s human

“The biggest red flag that I see is the anthropomorphization of AI,” Hao tells me, cutting straight to a core issue. This tendency to attribute human-like qualities to algorithms isn’t just semantic sloppiness — it fundamentally misrepresents how these systems function and serves specific industry narratives.

Consider how Silicon Valley frames LLMs as systems that “read like humans” to justify training on copyrighted works. “‘An artist ultimately is reading or looking at other art and then being inspired by it. And so AI works in the same way,’ the claim from the executives goes,” Hao explains. “Ultimately, that is not actually a good analogy for how AI works, because a lot of research has shown that these models [...] are not truly generating novel forms after seeing the older forms; they’re just remixing those older forms.”

This anthropomorphizing gives “AI” systems an undue appearance of agency and neutrality when they’re “an extension of what the creators of the AI tool and the users of the AI tool want to achieve.” The real actors — the companies, their leaders, their investors, their flocks of hype-repeating parrots, their users — conveniently fade into the background. (On that note, is the reason the style guide for ESC KEY .CO puts quotes around “AI” — underscoring that it is not intelligent nor it is not one kind of technology, while also using implying sarcastic finger quotes for fun!)

🚩 Using “AI” as a catch-all term

Equally problematic is Hao’s next red flag: using “AI” as a catch-all term without specificity. “There are many different types of AI technologies, and it’s really hard to understand which technology you’re talking about when you just use the term AI,” Hao points out. This blanket terminology obscures critical distinctions between vastly different systems with dramatically different impacts.

Take environmental effects. Some outlets publish stories claiming both “AI could be really bad for the environment, but it could also somehow help tackle climate change,” she’s noticed. And she’s dug into this in her own reporting — often claims from tech companies about some “future technology” might address some environmental issue. Not only is this vaporware. It often amounts to greenwashing. Last September for The Atlantic, she wrote about “Microsoft’s hypocrisy on AI.” She wrote then: “As Microsoft attempts to buoy its reputation as an AI leader in climate innovation, the company is also selling its AI to fossil-fuel companies.”

But in other cases, the framing can create a false equivalence that might lead understandably skeptical audiences to dismiss outright technologies that could actually help address environmental issues. The problem stems from the user of the term “AI,” as if we’re discussing the same technology in two different scenarios when we’re not.

The reality is more nuanced: generative “AI” models like GPT-4 require massive data centers, consuming extraordinary amounts of energy and water. Meanwhile, narrowly-scoped machine learning systems like those reducing airplane contrails operate on an entirely different scale, using predictive modeling and computer vision techniques requiring fewer resources. These targeted applications analyze weather patterns and flight paths to minimize contrail formation — a potentially helpful climate intervention using a different technological approach than the resource-devouring LLMs.

“It doesn’t really help us to say AI, generally speaking, is both good and bad for the environment,” Hao emphasizes. “That doesn’t point a path forward for how to resolve this conundrum when it’s actually quite easily resolvable once you determine, wait, you’re talking about technology A being bad and technology B being good.”

“So many so-called AI experts today are not actually independent experts.”

🚩 Not disclosing experts’ conflicts of interest

The third major red flag involves who gets quoted as “AI experts.” Too often, journalists cite individuals with clear financial stakes in the technology’s adoption without disclosing these interests.

“I think the last red flag that I see a lot is people quoting those who have clear financial or political interests as experts without actually revealing their ties to the economic or political gains that they might receive,” Hao says. This problem is particularly acute in “AI” coverage because “so many so-called AI experts today are not actually independent experts. Most people within the research field are actually doing their research within a company or receiving funding from ideologically or politically motivated organizations.”

The challenge for journalists is maintaining healthy skepticism without dismissing genuine expertise. As Hao suggests: “The best we can do, if we can’t avoid quoting those types of people, is to point out what kinds of hidden interests they might have or not-so-hidden interests they might have to say what they’re telling you.”

For readers, this means developing a habit of asking: Who benefits from this particular framing of “AI”? What specific technology is actually being discussed? And why are we still letting systems described as “intelligent” escape the responsibility of the humans who build and deploy them?

Three green flags that suggest you’re reading something with real teeth

If the red flags help you identify what to avoid, what should you actively seek out? What approaches illuminate rather than obscure? According to Hao, the markers of quality “AI” coverage are easy to spot, though — as with green flags in dating — not as commonplace as they ought to be.

🟢 Focus on the human stories

“Maybe the number one green flag is to really focus on AI as a human story,” she says. This approach grounds abstract technologies in concrete realities. “Because ultimately, AI is created by people and it affects people. And readers are going to be most interested and feel like they can relate most to the story when you’re telling the stories through characters.”

This human-centered framing isn’t merely about storytelling as much as it is journalistic accuracy. Stories that present “AI” systems as disembodied technical artifacts divorced from their creators, users and supply chain impacts fundamentally misrepresent the reality.

They perpetuate the Silicon Valley myth that these technologies emerge inevitably through neutral technical progress rather than through specific choices made by specific people with specific agendas.

🟢 Challenge inevitability narratives

Another crucial green flag: coverage that challenges the presumed inevitability of “AI” in its current form.

The current vision of “AI” — massive language models requiring data centers “the size of hundreds of football fields combined” — is presented as the only possible future. But this narrative serves those who’ve already invested billions in precisely that approach.

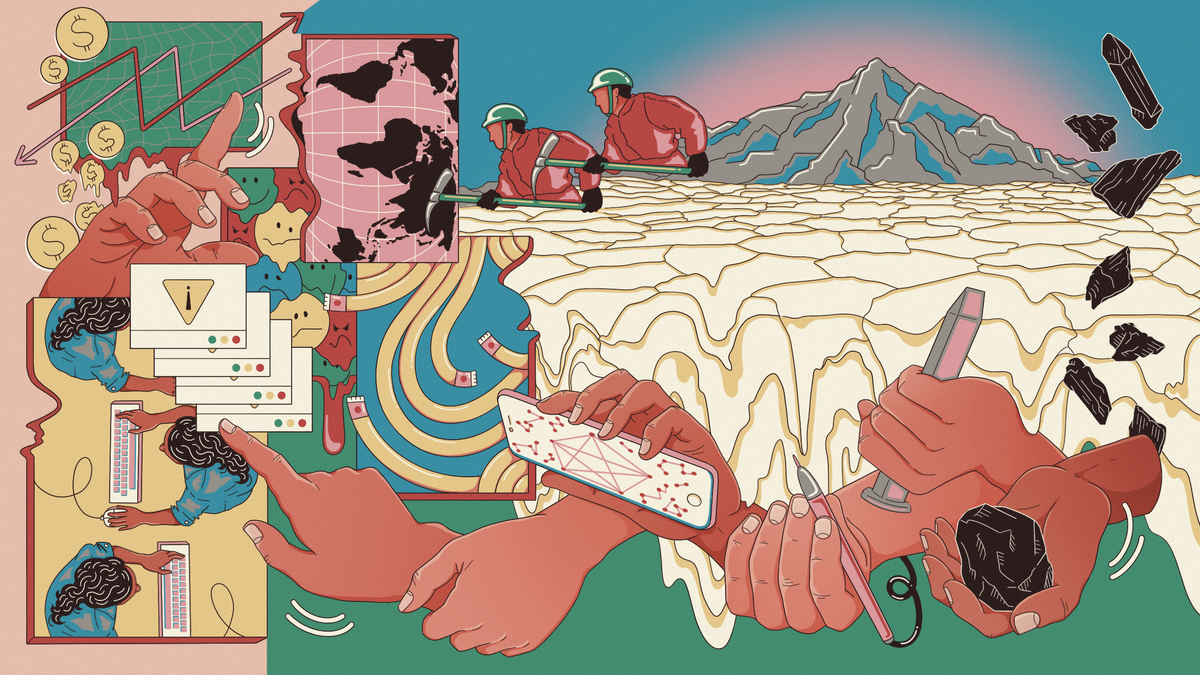

Quality reporting, Hao argues, examines the entire supply chain of “AI” development: “Who is actually collecting the data? Who is actually cleaning and annotating the data? What are the downstream effects of this kind of massive data collection?”

This approach unveils the hidden infrastructure — both technical and human — that makes current “AI” systems possible.

“There are real economies of extraction churning beneath the surface.”

🟢 Scrutinize the supply chain

“AI doesn't just arrive fully formed. There are real economies of scale, economies of extraction, labor exploitation and data exploitation that are churning beneath the surface to produce this technology in the first place,” Hao says.

This supply-chain perspective helps readers understand that current AI development models aren’t inevitable technological progress but specific economic and political choices.

Recognizing this opens space to imagine alternatives — “other types of AI technologies, maybe older forms of AI technologies that are not generative AI, that actually don’t use any of this supply chain, that operate on a very different type of supply chain.”

Try thinking about generative “AI” more like fast fashion (a product with real-world impacts)

Hao draws a compelling comparison to another industry where accountability journalism is key to informing consumers: “I sort of analogize it a little bit to fair trade and the fashion supply chain. There was such great reporting at the time on the fashion industry and how we do not actually need clothes that lead to human rights abuses.”

The most valuable “AI” reporting, then, resembles the best accountability journalism in any domain — it reveals power, identifies who benefits and who pays the costs, and challenges the notion that current arrangements are necessary or inevitable.

“The best accountability stories reveal that bigger picture and help ultimately empower informed readers and voters to essentially have agency in choosing which kind of AI tools they want and which supply chains they’re OK with,” Hao concludes.

In a media landscape dominated by press release regurgitation and billionaire hagiography, this kind of reporting remains frustratingly rare. But it’s out there if you know where to look.

And in its absence, the critical reading skills Hao outlines can help you navigate the hype with a clearer eye for what’s being obfuscated and, crucially, why.